Class of 1974 graduate tells the 40,000-year history of music through remains found in archaeological excavations

In celebration of World Music Day, we caught up with alumnus Dr Graeme Lawson (GDHons Archaeology and Music, 1974) to hear about his research into the origins of music as we know it through what has been left behind.

21 June 2025

Stumbling across an article in Newcastle University’s School of Archaeology about a recently discovered Anglo-Saxon string instrument inspired Graeme’s dissertation project, and consequently his lifelong career and passion for the material history of music culture. Today, Graeme is a world-leading expert in the origins of music through archaeological artefacts, working as a fellow at Cambridge University and publishing numerous books on the subject.

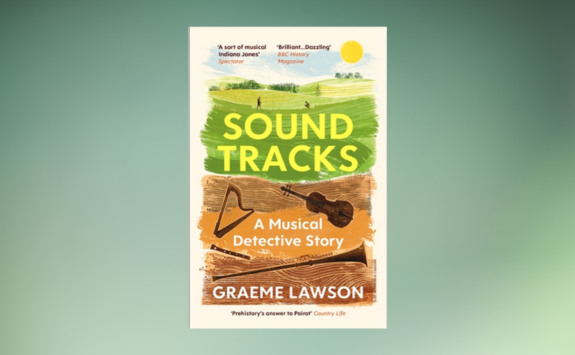

His latest publication is Sound Tracks, which traces the fascinating story of archaeologists’ explorations of music's prehistory, from the present day back to the first modern humans and beyond.

To mark World Music Day 2025, we caught up with Graeme to hear more about what we can learn about music making through the ages from the archaeological evidence left behind and where life has taken him since leaving campus in 1974.

Hi Graeme, thanks for speaking with us this World Music Day. What was Newcastle like for you as a student in the 70s?

I have to say that Newcastle was where it all took off for me, under the guidance of musicologist Benedict Sarnaker, the prehistorian George Jobey and professors Denis Matthews and Martin Harrison.

Big changes were happening in Newcastle as I arrived on campus in the early 1970s. Before then, the city was still (let’s be honest) a bit grimy – many of the buildings were still coated in black soot and the tangle of wires suspended above the streets for the old electric trolley bus system had only just been dismantled. I suppose it was the very end of that post-war era.

But it was just as friendly a place as it is today, and I found the same applied to the people on my course. Undergrad friendships tend to stay with you for life, and I’m still in touch with nearly all my contemporaries from both departments. We’ve reunited a number of times over the years, most recently in Rothbury just after the first Covid lockdown. We really should have organised something last year for our 50th anniversary, but I think we’re all just a bit shell-shocked by the fact!

I remember keenly the anxiety of going under the Arches to check my final degree results 50 years ago. I must admit that my final exam grades were a bit disappointing, but my dissertation went down very well – so well, in fact, that when we approached Cambridge University to ask if they were interested in it, they almost took our hands off! So that’s how I came to migrate to Cambridge to research my PhD.

It's a sadness today to see that the Museum of Antiquities, which in my day stood alongside the Arches, no longer occupies that prime spot on campus. But the thing that I never quite forgave Newcastle for was knocking down the Haymarket pub! We had many a happy seminar in there, and the lady who swept up at closing time had to come round and hack at our ankles with her broom to try and get us to leave! Together with the nearby Plough, it became a common room of sorts for us. We had an actual common room, of course, but The Haymarket sold beer!

We’ve heard many stories from the Haymarket pub from fellow alumni! Where else did you visit often in the city?

I have fond memories of heading to St. James’ Park on a Saturday to watch the football, and the trainspotters among us would spend many a happy hour in Central Station, usually followed by coffee and a Wagon Wheel in the Lit and Phil.

We also used to hang out at Pumphrey’s on the Bigg Market, next to what was Balmbra’s Music Hall. Pumphrey’s was very old-fashioned and quaint, with the tea shop downstairs and restaurant upstairs. There were little cosy cubby holes where you could congregate with your friends. It was a sad day when that closed, I have to say.

Having grown up in the North East, I was living (nominally!) at home as a student. But it was great being able to introduce my friends to the Northumberland beaches at weekends – when we weren’t exploring up-country or fell-walking in the Lake District. We also enjoyed fishing trips at Close House, a little bit of heaven on Earth.

How did you get into telling the archaeological history of music?

At first, my undergraduate dissertation focused on archaeological finds from the 5th to 7th centuries, but it snowballed from there. In those days, few people seemed to be studying the dirt-archaeology of music, so it kind of became my signature throughout my career: not just the archaeology of musical instruments, but of music and musicians too – the overall history of music.

Nowadays, there are many of us around the world studying this subject and we meet up regularly for conferences. My latest book, Sound Tracks, is my attempt, as one of the early researchers in the field, to capture a sense of the whole archaeological story of music’s origins and evolution through time as we see it unfolding – and how we know what we now know.

Sound Tracks is my attempt to capture a sense of the whole archaeological story of music’s origins and evolution through time as we see it unfolding – and how we know what we now know.

What was the most exciting discovery you came across in your research for the book?

It’s hard to single out one, but one of the most remarkable has to be a lyre that was found in the early 00s - in an Anglo-Saxon princely tomb in the middle of a roundabout in Essex. Around 20 years before the discovery, I was turning up fragments of a similar sort in museum collections and conservation labs, but we could only imagine was the complete instrument must have looked like.

As the excavation reached the floor of the burial chamber, the lyre appealed as a pattern of wood and metal fragments within a dark shadow in the sand, and we could see the complete shape for the first time. It was amazing to see with my own eyes how closely the original instrument resembled the replica I had constructed from only those earlier scraps. It’s always satisfying to have a prediction proven right!

Lyres have popped up in ‘ordinary’ graves around the country too: it’s clear that lyre-playing was endemic. But the evidence is also beginning to suggest that what we're seeing in them is not just music, but a footprint of poetry, because we know from Anglo-Saxon literature that the lyre – a ‘harp’ or ‘cithara’ in those days – was an essential accompaniment to Old English verse. Before the advent of widespread writing, it was the poets who were recording events, and celebrating stories, who were the guardians of an oral history and a shared knowledge of the world.

And what about the oldest musical artefacts that have been found? When does the history of music date back to?

The hard evidence we have currently dates back 40,000 years and the oldest instruments we find are pipes with finger-holes made of bone or even mammoth ivory. Some are still intact, which means we can reconstruct their tunings and have a stab at recreating the combinations of sounds they were making!

It's very exciting to hear their voices coming to us out of the distant past. While we can never hear the human voices, we can at least hear what they were articulating with their music.

What you quickly discover is that early civilisations were capable of really elaborate music making, much more elaborate than we might otherwise give them credit for. For example, in the Bronze Age, they were making large, elegant metal horns that are difficult to make today even with modern technology!

It challenges our ideas about what people’s lives were really like. They were clever, ambitious people – they weren’t living in squalor. That’s often the impression you get with archaeology as everything is coming through mud and silt. Colour is often missing from prehistory, but with musical instruments we get back some of that spirit of vitality: a sense of the pleasures that people had alongside all the hardships.

Colour is often missing from prehistory, but with musical instruments we get back some of that spirit of vitality: a sense of the pleasures that people had alongside all the hardships.

Sound Tracks has recently been released as a paperback. You must be very proud! What is the proudest moment of your career so far?

Throughout my career, I’ve done an awful lot of reporting on archaeological finds, editing books and attending conferences. But it tends to be isolated sections of the whole picture – a specific type of music or instrument, or a singular era. What was needed was something that would tie together the whole picture and show a journey of music through time. That’s what Sound Tracks is, and I’m immensely proud of having this book published by Penguin.

I think there’s a perception in the world that most research that can be done has been done – but we’re just scratching the surface. There is a whole world of fascinating mystery and opportunities for today’s students writing their dissertation just as there was for me 50 years ago!

With Sound Tracks, I hope the reader will get a flavour of what it's like being an archaeologist studying music: what the challenges are and where the excitement and joy is. I hope it will inspire the next generation of music historians to take a look at archaeology and the astonishing insights it can offer.

Maybe some will come from our very own campus! Thanks for speaking with us Graeme, and happy World Music Day!

About Sound Tracks

Sound Tracks tells the history of our relationship with music in sixty detective stories, each focusing on the discovery of a musical instrument (or its fragments) in archaeological digs around the world. Guiding us from the present day all the way back to the dawn of humanity, long-lost music is itself reconstructed as we enter the worlds of those who created it.

Graeme Lawson takes us on a grand tour of some of the world's greatest musical discoveries, revealing that music is part of our human DNA - not just in its role as a pastime, entertainment or religious expression but also as a medium in which we commemorate our pasts, communicate with each other, and shape our identities, relationships and communities.

Available to purchase in paperback now from all good bookstores.

Do you have news to share with our alumni community?

Get in touch and share your latest news and achievements so we can let your fellow Newcastle alumni know!