Getting to Know Chinese Characters Through “Drawing”

9 February 2026

A Case Study of Character Instruction in an After-School Chinese Club at a UK Primary School

Background

This lesson took place in an after-school Chinese language club at a primary school in Newcastle, the UK. The classroom was small, with nine children sitting around a long table. The students ranged from Year 1 to Year 4 and came from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds: two were of mixed Chinese–British heritage, two came from Chinese families but had grown up in the UK, and five were local British students with no prior exposure to Chinese.

The class met once a week for one hour. There was no fixed syllabus; instead, the core goal of the course was simple—to spark children’s interest in the Chinese language.

At the beginning, I attempted to teach students to write Chinese characters. However, I quickly noticed that the word “write” itself caused some children to frown. Before their pencils even touched the paper, someone would quietly say, “It’s too hard.” In contrast, the children naturally asked, “Can I draw the character?” Over time, “drawing characters” became the default expression in the classroom. This made me realize that for young learners, Chinese characters should not first be treated as symbols that must be “written correctly,” but rather as images that can be “drawn.”

Teaching Process

With this in mind, I designed the lesson around the idea of drawing Chinese characters. On the blackboard, instead of demonstrating complex stroke orders, I first guided the children to observe the overall shape of each character. For example, I asked: What does the character 山 (mountain) look like? Some children said it looked like three small mountains; others traced the rising and falling outline in the air with their fingers. When we looked at 人 (person), one child immediately stretched out their arms, mimicking a standing posture. Through discussion, the characters gradually became visual, imaginable, and physically relatable forms.

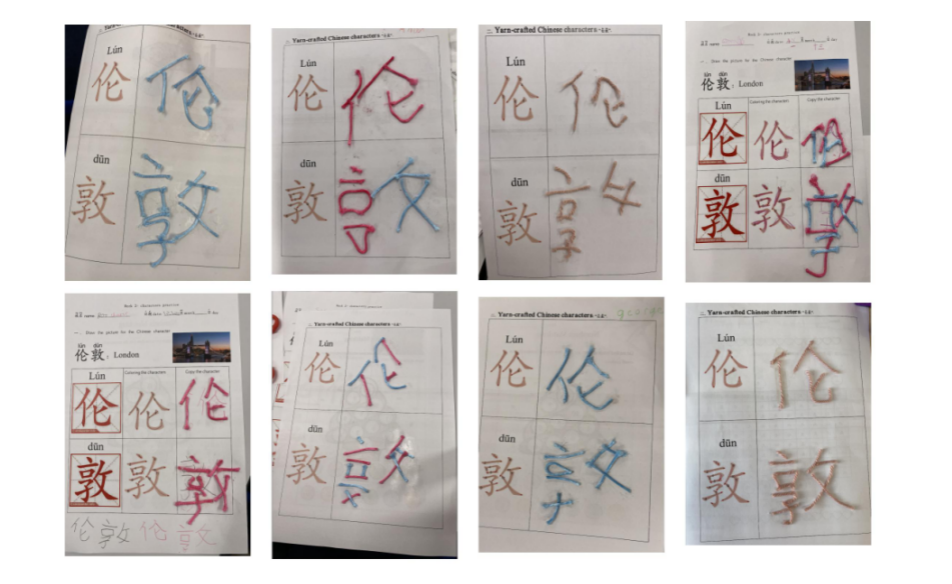

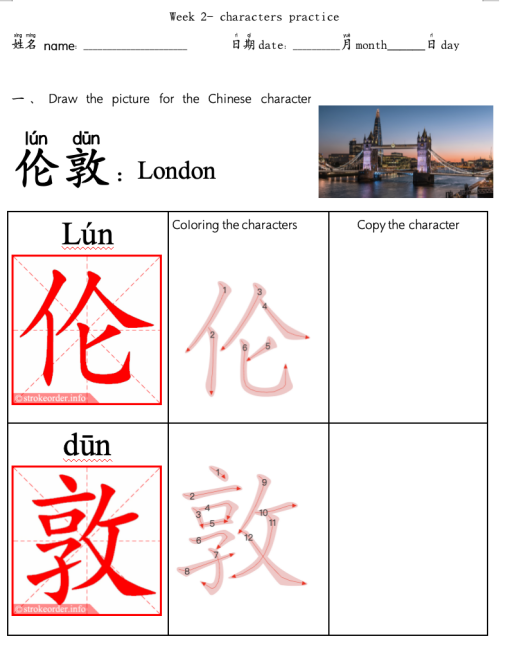

Next, I brought out materials I had prepared in advance: colorful yarn, scissors, and glue. The children’s eyes immediately lit up. The task was simple—choose one character and “draw” it using yarn. The process of cutting, arranging, and gluing was quieter and more focused than I had expected. Some children repeatedly adjusted the position of the yarn, trying to make the structure look “more accurate.” Others asked questions such as, “Is this part inside?” or “Should this be a bit higher?” These questions reflected their developing awareness of the spatial structure of Chinese characters.

Learning Outcomes

During this process, differences in students’ linguistic backgrounds became far less noticeable. Even students with no Chinese language background were able to understand character composition through hands-on manipulation. After completing their work, every child was eager to hold up their creation and proudly say, “This is my character.” Some were even able to pronounce the characters “shan” and “ren” in simple Chinese.

From a teaching perspective, this progressive learning path—from observing, to coloring, to drawing, and finally to assembling—did not lower learning expectations. On the contrary, it provided young learners with a more accessible entry point into character learning. Through tactile activities such as yarn collage, Chinese characters were transformed from flat written symbols into adjustable, three-dimensional structures, helping students understand spatial relationships through physical engagement.

Post-Lesson Reflection

In my post-lesson reflection, I realized that “drawing characters” does not mean simplifying or lowering standards but rather opening a more welcoming door to character learning. Yarn collage activities turn characters from abstract symbols into tangible, malleable structures. This hands-on approach helps children grasp spatial relationships while effectively reducing anxiety toward character writing.

In terms of teaching materials, the lesson was not limited to paper-and-pencil writing. Instead, a wide range of materials—such as yarn, pipe cleaners, toothpicks, and even blueberries or cherries—were introduced to make character learning more open-ended and engaging. Through repeated placement, adjustment, and combination of materials, students were able to intuitively perceive the spatial structure and overall aesthetic of Chinese characters, laying a sensory foundation for more standardized writing in the future.

In after-school Chinese programs at UK primary schools, interest matters more than accuracy. When children are willing to draw Chinese characters and feel close to them, the journey toward truly writing them can begin.