Newcastle gaol

Prison break - new research aims to free the history of Newcastle gaol

Published on: 20 November 2019

The grisly history of Newcastle’s notorious Victorian gaol is being brought to life by a new research project.

Rich legacy

Experts at Newcastle University are researching the stories behind some of the prison’s inmates, their escapes and executions, in order to capture a bygone piece of the city’s heritage.

The project is being launched to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the last execution to take place in Newcastle. On 26 November 1919, just months after returning from service with the Royal Air Force, Ambrose Quinn, 28, was hanged for murdering his wife whom he had suspected of being unfaithful.

Six years later the gaol, which was located in Carliol Square, was closed and the building was demolished.

Dr Shane McCorristine, Lecturer in History, Newcastle University, said: “Newcastle gaol may be long gone and very few signs of the gaol or any of the city’s places of execution remain. But the area around Carliol Square has a rich legacy associated with the criminal justice system.

“We know that in its final years, the gaol was surrounded by homes, pubs and even a school. We want to hear from anyone who has any memories that can help us tell the story of Carliol Square and the history of crime and punishment in Newcastle.”

Changing attitudes to punishments

One of the gaol’s earliest inmates was also one of the most infamous. In January 1829 Jane Jameson, a fishwoman who lived on Sandgate, on Newcastle’s Quayside, killed her mother in a drink-fuelled argument by stabbing her with a hot poker.

At her trial, Jameson was found guilty and sentenced to death followed by public dissection. Post-mortem punishments for murder had been introduced in 1752 and could be either in the form of gibbeting or public dissection. And although judges were required by law to say what post-mortem punishment should be given to offenders, the dissection of a female prisoner was very unusual - Jameson was the last woman to be dissected in the city.

Several years later, attitudes towards capital punishment began to change and demands for prison reform, including the abolition of capital punishment, gathered force from the mid-nineteenth century. The last public execution in Newcastle took place in 1863, after which they took place in private behind the walls of the new gaol.

"A nest of villainy"

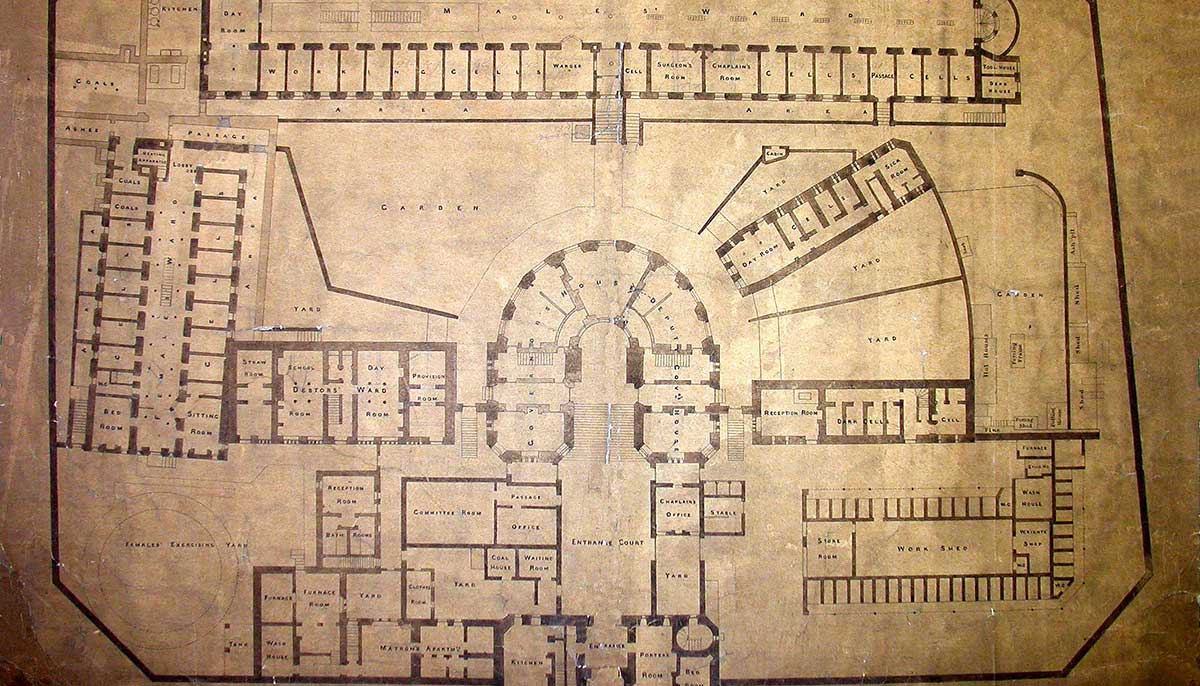

Approved by an Act of Parliament and designed by John Dobson, Newcastle gaol was among the first prisons to use a radial ‘panopticon’-style system, seen as a modern and progressive design that would help reform rather than punish offenders.

However, the high construction costs meant that only five of the six radial wings were ever built. It opened in 1828 but within ten years of it opening the gaol was condemned for being damp, rat-infested and overcrowded, and several escapes had taken place.

Dobson’s original design was an imposing structure, with a fortress-style central tower, formidable entry gate and 40 foot high walls. But 30 years later, due to the poor conditions and rapidly expanding prison population, Dobson was asked by the council to gradually pull down the wings and replace them with a single four-storey block of 144 cells, for a third of the original construction costs.

Dr McCorristine explained: “A lot of the issues the prison was facing were down to its location near the centre of a rapidly expanding city. The prison population soared due to the population growth Newcastle was experiencing at the time, as well as a general increase in policing and punishment of urban and poverty-related crime.”

Conditions in the gaol were intended to be strict – communication with other prisoners was banned, as was the bartering of provisions. Prisoners were required to carry out hard, monotonous work which if they successfully completed could earn them a slightly better diet and a hammock to sleep on instead of a ‘plank’ bed.

In reality, however, prisoners were able to openly meet and talk to each other. Debtors were also imprisoned in the gaol although under different conditions – they were able to receive visitors every day instead of once every three months and were given three pints of ale a day, which they used to sell on to other prisoners. This lack of policing in the gaol prompted criticisms of it having become a “nest of villainy” that offered few opportunities for reformation.

The work being carried out by Dr McCorristine, part-funded by the Catherine Cookson Foundation, builds on an earlier analysis of the gaol’s inmates by Newcastle University graduate researchers Megan Adams, Annie Padgett, and Dotty Walker. Using archive information held by Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums they found that throughout the 1860s and 1870s, the majority of inmates were aged between 16 and 25 but a substantial number of children – some as young as nine – also ended up in the gaol.

The analysis also showed that theft was the most common crime and that most prisoners were from Newcastle and Gateshead, although a significant minority were Scottish and Irish, reflecting wider changes in the city’s population at that time.

The information uncovered by Dr McCorristine and his colleagues will be shown in an exhibition next year and will also be made available on a dedicated website.

Anyone with stories or images connected to Newcastle gaol can get in touch with the research team by emailing: shane.mccorristine@ncl.ac.uk