Shipping

Post-Brexit future for shipbuilding

Published on: 6 November 2017

Experts call on the Government to put the past behind us and invest in an industry that could have positive economic and societal benefit in the 21st century.

Thatcher not to blame for the demise of our shipyards

Responding to the Government’s National Shipbuilding Strategy, former shipbuilder and Newcastle University lecturer Paul Stott says the decision to focus our future efforts almost entirely on naval ships and to ignore the commercial sector is a mistake.

Speaking ahead of his public lecture – ‘Whatever happened to our shipbuilding industry’ – Dr Stott says he believes that the political view of the industry and its prospects are coloured by the difficulties that characterised most of the twentieth century, not only the 1980s.

“Commercial shipbuilding, like coal mining, is something of a political pariah, based on the difficulties of the twentieth century,” explains Dr Stott.

“The final decline of Britain’s shipbuilding industry was already well underway when Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979.

“Our market share had been declining over the whole 20th Century and by the early 80’s there was little we – or Margaret Thatcher - could have done to save it.

“That is now history, but our vision for the future of the industry is too often formed with one eye in the rear-view-mirror.”

Missed opportunities post-Brexit

If we abandon the prospects for commercial shipbuilding completely, says Dr Stott, we are at risk of finally ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’.

“We risk missing out on an opportunity to gain value from the commercial sector to support our naval shipbuilding strategy in the future and this will be of particular importance in a post-Brexit world,” he explains.

“Many factors were to blame for the demise of the industry. Shipbuilding changed radically after WWII and our labour and investment was the wrong shape for the new world order, with little appetite for the massive investment that would have been needed to maintain dominance. Globalisation also happened and our imperial core home market disappeared.

“We are not about to become a global market leader again but that does not mean to say that we cannot gain value from commercial shipbuilding in specific sectors, such as ferries or research vessels like the David Attenborough under construction at Cammell Laird.

“And we will succeed best with an industrial policy that embraces the opportunity and positively supports investment and development – as our main EU competitors enjoy.”

Rose-tinted spectacles

Discussing the attachment the North East and other shipbuilding regions have to the industry that has gone, Dr Stott says there’s a tendency to look at the past through ‘rose-tinted spectacles’.

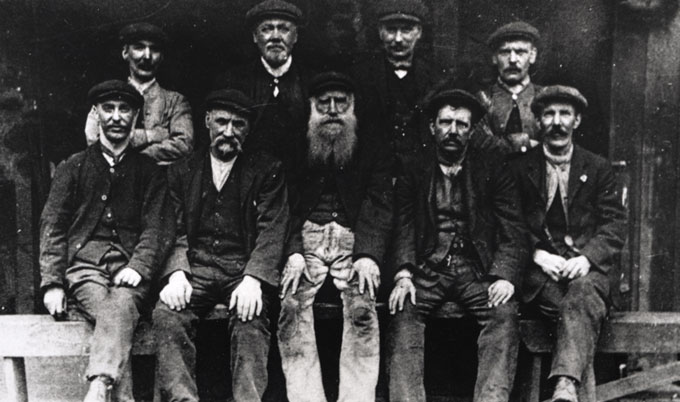

“Historically, shipbuilding was an inherently hard industry, and the shipyards claimed hundreds of lives and maimed many more in the Victorian and Edwardian heyday,” he says.

“Job security was also non-existent in a volatile industry, culminating in the Jarrow March, at which point over 80% of Tyneside’s shipyard workers were unemployed. The attachment of former shipbuilding regions to the industry is therefore hard to understand.

“But shipbuilding is personal and even now, in areas like Tyneside, Wearside and Clydeside, many families still have a link with the shipyards.

“Generations depended on the industry and despite the hardship, we look back on it through rose-tinted spectacles and feel that we are somehow to blame for its failure. It is the society that we miss, however, more than shipbuilding itself, stemming from the very strong social infrastructures that developed around the shipyards.”

The social structures, says Dr Stott, were made even stronger by large numbers of workers united in difficult work and with a common purpose.

Now, against a backdrop of Brexit and renewed competition with the EU, Dr Stott says we need to take a fresh look forwards at what can be gained in the commercial sector.

“We still have the potential to develop niche areas of commercial shipbuilding here in the UK and while I’m not suggesting we can return to our shipbuilding heyday, there is national value to be gained from this sector.

“But the Government needs to be brave and put the past behind them. Instead, we need to stop blaming ourselves and fearing failure and look at where we can make a real impact and push forward technological innovation in commercial shipbuilding – with positive benefits for the naval shipbuilding strategy that has recently been published.

“The history and heritage is important, but only in the context of history. We need to take a fresh look forwards to identify the viable future and to re-invigorate this once great British industry to gain the economic and societal value that is relevant to the 21st Century."

‘Whatever happened to our shipbuilding industry?’, by Dr Paul Stott, naval architect and shipbuilder and senior lecturer, is part of Newcastle University’s Insights Public Lecture series. It will take place on Tuesday, November 7, at 5.30pm in the Curtis Auditorium, Herschel Building. Free admission and open to all.