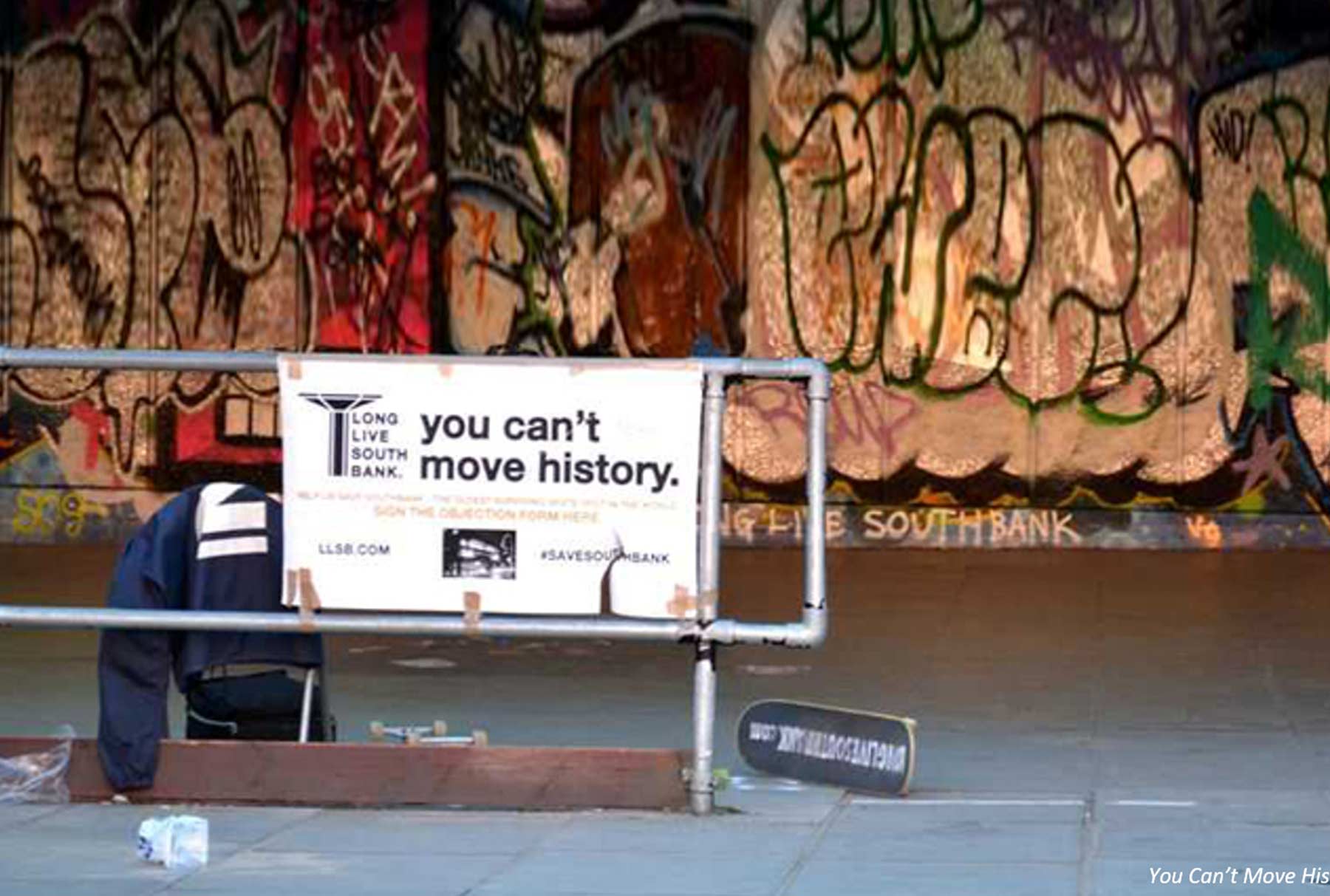

You Can't Move History

Engaging young people in cultural heritage through a collaborative project.

Our built heritage provides a link between the present and the past. It contributes to the design and the interest of places we use on a daily basis and it records expressions of skills, crafts, materials and industries which in many cases have been left behind. But heritage is more than just a resource used to enrich our society.

Heritage is also an effect of power imbalances and social conflicts which evolve over time. Dominant ideas about what counts as legitimate heritage change over time and they ultimately represent the views, either of professionals or of politicians and activists who have successfully lobbied for change.

While young people have often been asked to fill in surveys and questionnaires about what kinds of heritage they value, there have been very few examples where they have been able both to conceptualise heritage in their own terms and win influence for this conceptualisation. The Long Live Southbank campaign is an exception to this rule.

About the research project

This research project involved a collaboration between academics from four different UK universities, the film-making collective BrazenBunch and the campaign group Long Live Southbank.

The core of the project was the creation of a 22-minute film documenting a campaign which, in September 2014, successfully secured the preservation of a 40-year-old skate spot on London’s south bank.

Known to many from one of the arenas in the computer game Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4, the undercroft has been an iconic part of the skateboarding scene since it first arrived in the UK. It is associated with two impressive titles: the UK’s oldest surviving skate spot and the location of the most unpopular planning application yet recorded. This second accolade was achieved with the help of the campaign’s tag line 'You Can’t Move History'.

Coming in shortly after the campaign’s success, the academics involved in this project were interested in better understanding the unique heritage claims which had been made by those involved. There was also an action-research motivation to the work, with the film being divided into three sections exploring how skateboarders understood their connection to the space, how they sought to communicate that to others and the extent to which they were heard.

This format was intended to provoke reflection among an audience of heritage professionals and policy makers at a workshop held in 2015. Following some successful negotiations, Long Live Southbank launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise funds to restore the skate area to its original, larger size. The results of the research have been accepted for publication in the International Journal of Heritage Studies and the project’s film won first prize in the 'Best Research Film' category of the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s 2016 Research in Film awards.