“We are going to get all our oil and gas out of the North Sea”, Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch said recently. Her promise to “maximise extraction” sets up a clash between political ambitions, economic reality and geological limits.

Reform UK has also said drilling for more oil and gas in the North Sea would be a “day one” priority. But even if the Conservatives or Reform were to be elected and lifted the current moratorium on new exploration licenses, there might not be the promised prizes of oil and gas under the seabed – or enough appetite from investors – to deliver on that promise.

BP, in those days British Petroleum, first extracted gas from under the North Sea in 1967. It marked the start of what was to become, for decades, one of the most valuable sectors of the UK economy, with more than 400 separate oil and gas fields developed to date.

But production peaked in 1999 and the North Sea now produces less than half as much as in its heyday.

It is now a “mature” basin: most of the biggest and easiest-to-develop fields have already been discovered and depleted. What remains are smaller, sometimes more remote, and often more technically challenging or expensive resources and reserves.

This is typical of ageing oil and gas provinces, where production declines even as operating costs rise. New projects must compete with oil and gas extracted from other parts of the world where it is easier and cheaper and more appealing to investors.

Finding oil and gas

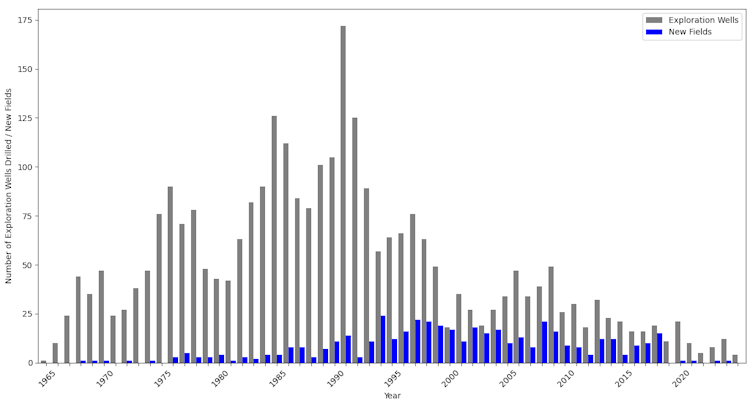

Historically, only one in eight exploration wells in the North Sea led to a field producing oil and gas. That ratio has improved: between 2008 and 2017, a bit more than one in four wells led to a commercial success.

But far fewer wells are being drilled today. Even with the advances in technology, such as improved geophysical imaging which allows us to better define opportunities ahead of drilling, the big discoveries were probably made decades ago.

UK exploration wells vs offshore fields by year:

The UK government’s North Sea Transition Authority estimates there could still be around 3.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent in more than 400 undeveloped prospects. But most of these potential fields are small, isolated or technically complex. Developing them will require high oil and gas prices, fiscal stability, and a lot of investor confidence.

Politics vs geology

Even if a future government relaxes exploration licensing rules, geology will remain the bigger constraint. The North Sea is simply not as cheap as it was, and global fossil fuel giants have many other options. It is currently far cheaper to produce oil and gas in other regions, the Middle East or North Africa for example. Projects in these countries are all competing for the same capital.

Volatility in the energy sector will continue to make investors cautious. The 2015 oil price crash cut activity in the UK sector to its lowest level in decades, and it has never fully recovered. As fossil fuels are sold on the global market, political volatility, international and national, can lead to rapid shifts in investor confidence.

In the UK the introduction of a windfall tax in 2023 and changing requirements for environmental impact assessments are all making decision making on long-term projects riskier. And while the UK still needs considerable volumes of gas in future (and more modest amounts of oil) both are declining as our energy system evolves and renewable energy expand.

The UK’s mix of economic uncertainty, mature geology and smaller discoveries will make it harder to attract major international energy firms.

The future of the North Sea

That doesn’t mean the North Sea has finished as a source of oil and gas. For instance, undeveloped discoveries – where oil or gas has been confirmed but not yet produced – represent a lower-risk opportunity. But returns may be modest as many are relatively small and isolated from existing infrastructure.

New exploration licenses, if issued, might extend production modestly, but they are unlikely to deliver another game-changing discovery.

Some analysts argue that future licensing should be highly strategic, limited to projects with clear economic importance or climate compatibility. That approach could reduce reliance on imported gas, which tends to be more carbon-intensive than gas produced domestically. This would certainly make more sense than restarting fracking. But it would still not recreate the industry’s heyday.

Easy oil is over

The North Sea will still produce oil and gas for years to come, but its role will shrink. Even with friendlier policies, the era of big discoveries and rapid growth isn’t coming back.

Maximising extraction may sound appealing to politicians, but geology, economics and climate commitments all point to the North Sea’s best oil and gas days being behind it. The real challenge now is managing the investment during decline while investing in the cleaner solutions that will replace it.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Mark Ireland, Senior Lecturer in Energy Geoscience, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.