Gender-Inclusive Language

How to recognise and avoid gendered biases and sexist language.

Double standard

- ‘A rule or standard of good behaviour that, unfairly, some people are expected to follow or achieve but other people are not.’

- ‘Applied specifically to a code of sexual behaviour that is more rigid for women than for men.’

– Cambridge Dictionary

Women’s and men’s sexual conduct is not viewed identically by society. This double standard is visible in language. One easy way to identify it is to look at slurs specifically used about women and ask: is there an exact equivalent for men? One example of double standard is titles; another is slurs.

One respondent recalls that, over a period of six months, while being out at different times of the day, she was called by strangers ‘slag’, ‘cunt’, ‘slut’ and ‘bitch’:

‘… it felt like a total assault on me as a woman. And I recognise there’s massive degrees… it’s not sexual violence, it’s not physical violence, but it just felt like… it just felt horrible, actually.’

Respondents mentioned bitch and slag. At least originally, both target a woman’s supposed ‘excessive’ sexual activity to demean her. There is no such word to condemn a man’s behaviour. In fact, it would often be considered as sexual prowess. The off-hand use of these slurs can be viewed as part of rape culture.

Bitch and slag are similar but not identical in their use.

Slag is always derogatory and is particularly prevalent in lad culture.

Bitch is sometimes used without real derogatory intent, as in the expression resting bitch face and in African-American English. If used among women, it is sometimes used jokingly, in a friendly way.

Terms of address

Girls, guys

- Girls can be seen as belittling when used about adult women in certain contexts.

- Guys can be gender-neutral. It can refer to men and/or women indifferently. But this interpretation depends on the variety of English at stake. In England, not everyone perceives it as gender-neutral.

We group these two words for obvious reasons: each are used about members of one gender group, either women or men – or so it seems at first.

Girl(s) was the second word our respondents brought up the most, with explanations such as:

- ‘has a derogatory meaning when used to describe any female over the age of 16’

- ‘because in my immediate work environment (colleagues and students), as well as in society at large, women are being referred to as girls, thus belittling them and keeping them subjugated’

- ‘people use the term girl when talking about grown woman particularly in admin roles; it is demeaning’

- ‘women in the workplace are often referred to as girls, while men are almost never referred to as boys in the same way. While most people do not probably find this offensive/mean to be offensive, it is still belittling’

- ‘often used lazily and pejoratively and implicit weaker sex stuff’

Respondents describe girl(s) as ‘belittling’ and ‘derogatory’. To understand the problem, it is important to note in which in which contexts using girl(s) might be questionable.

Respondents mentioned, for instance, use of the word in a work environment, and for ‘grown women’. In an interview, someone described the word as infantilising when used by staff members about students. Newcastle University’s Everyday Sexism Report, published (June 2019) quotes Sophia, an undergraduate. She recalls a lecturer ‘who used to call women “sweetie”, “girl”, “doll”, and explained all answers to them in a condescending tone that the boys never got’ (p5). Niamh reported hearing a friend referring to a lecturer as ‘that girl who teaches…’ In these situations, girl(s) is not used about peers.

Declaring that you are ‘going out with the girls’ is quite different from using the word about one of your students, or one of your lecturers.

Another respondent wonders:

‘whether “girl” and “guy” are equivalent or whether “girl” is more diminishing (?) and whether it is/should be acceptable to refer to women up to the age of, say, 30 as “girl” without using the word “boy” for men of the same age.’

Guy(s) and boy(s) are not used in the same way. Neither is the exact equivalent of girl(s) when used about adults. Boy can sound juvenile, or is used in a friendly, affectionate way (‘I’m going out with the boys’). Guy is always casual. It is increasingly used to refer to mixed-gender groups, or even to women-only groups. As linguist Deborah Cameron puts it,

‘“Guy” is no longer uniformly sex-specific. The plural form, guys, has become gender-inclusive in one subset of its functions – when it is used as a vocative, as in “Hi guys”, or more broadly to address people in the second person, as in “What are you guys doing tonight?”’

Respondents were aware of this change but felt ambivalent about it:

- ‘Not used formally very much (or indeed at all) but used a lot informally. I'm unclear about how this sits in terms of inclusive language, having read very different takes on this from linguistics scholars as to whether this is gendered language.’ [male respondent]

- ‘This is a word I often hear used, and also find myself using, to informally address mixed gender groups. I wonder to what extent this terms is perceived as male-gendered and should be subject to the same critique as earlier universalising uses of the term 'man' in more formal speech.’ [male respondent]

- ‘I believe this is evolving into a non-gender specific term for a group. But it is is important to understand that some people may not share this view and still view this as a gendered word.’ [female respondent]

Cameron also explains that dude in American English and mate in Australian English seems to be undergoing the same process of de-gendering. This is a change driven by young women, who recognise themselves when addressed as ‘Hi guys’. According to her, this is because women want:

‘… to express the same attitudes and feelings men have traditionally used them to express, like camaraderie, solidarity and ‘mateship’. The fact that these attitudes and feelings have historically been associated with men does not mean they are inherently male (any more than historically male-dominated endeavours like science and sport are inherently male). Rather they are part of the repertoire of human attitudes and feelings.’

Nonetheless, it seems important to note that not everyone feels comfortable with this term of address. Lecturers, for instance, might want to avoid using it when addressing students.

References

Cameron D. The illusion of inclusion. Language: a feminist guide (blog). 5 August 2018.

Other gender-specific words

Gender, as a system, does not only class us as either man or woman. It also confers to us certain attributes, and the social values behind such attributes.

Here are descriptions of Jane and James. Only the names and pronouns have been changed. Read Jane’s description before James’.

Jane is a lovely, smiley, bubbly girl of 22. But what people admire most about her is how feisty she gets when it comes to her career. Having completed a Masters in Politics, she is starting a new job. She is very driven and is already managing an intern, John. John sometimes complains to his friends about her bossiness, and Jane’s colleagues often describe her as being aggressive in her job. Sometimes, however, she displays emotional outbursts and over-sensitiveness about how she is treated in the workplace. Some even call her behaviour irrational.

James is a lovely, smiley, bubbly boy of 22. But what people admire most about him is how feisty he gets when it comes to his career. Having completed a Masters in Politics, he is starting a new job. He is very driven and is already managing an intern, John. John sometimes complains to his friends about his bossiness, and James’ colleagues often describe him as being aggressive in his job. Sometimes, however, he displays emotional outbursts and over-sensitiveness about how he is treated in the workplace. Some even call his behaviour irrational.

- How do you react to the first description? To the second?

- Do you think both are equally likely?

- How would you pinpoint the difference between the two?

The problem is not that there are different words to talk about people of different genders. We need to be conscious of how those words are used and what connotations they convey. Linguists have found time and time again (Hellinger and Bussmann 2001, Pauwels 2008, Hellinger 2011, Sczesny & al. 2016) that words specifically associated with women convey values that are not as well considered by society as those associated with men. They call this semantic derogation. This is the process of using negative connotations to belittle someone. This phenomenon often has to do – as is the case with double standards – with sexual behaviour.

Consider the word master and its supposed equivalent mistress. They are etymologically paired, yet one, mistress, has sexual connotations absent from the other. This is why mistress tends to be avoided outside of the context of marital affairs, and master is often used today in a gender-neutral way, to refer to a man or a woman. We can reach other arrangements, like saying headteacher instead of headmaster/headmistress

This semantic derogation is due to the fact that gender, as a system, does not only class us as either man or woman. It also confers to us certain attributes, and the social values behind such attributes. Historically, values associated with women have been regarded with less prestige, less authority, and sometimes with downright negative connotations.

There are other ways in which gender appears in language. Some languages have grammatical gender. Nouns and pronouns are divided between classes (masculine, feminine and/or neuter). For instance, moon is feminine in French (la lune) but masculine in German (der Mond). This was historically the case with English. Gender is still encoded in certain words, for example words expressing kinship (mother, father, daughter, son…). English has also kept traces of this history in suffixes (a unit added at the end of a word), for instance –ess and –ette.

Consider the pairs of words below. Which words can we apply equally to men and women? (adapted from Goddard and Patterson 2000:61).

Usher : Usherette

Actor : Actress

God : Goddess

Waiter : Waitress

Mayor : Mayoress

Now consider these two columns. Why is gender specified in the right column but not in the left? (adapted from Goddard and Patterson 2000:60-61).In the pairs above, the words on the left were historically masculine, but can now be understood to refer to any gender. But the words on the right can only ever apply to women (see masculine used as generic).

Nurse : Male nurse

Prostitute : Male prostitute

Doctor : Female doctor

Secretary : Male secretary

Scientist : Female scientist

Lawyer: Female lawyer

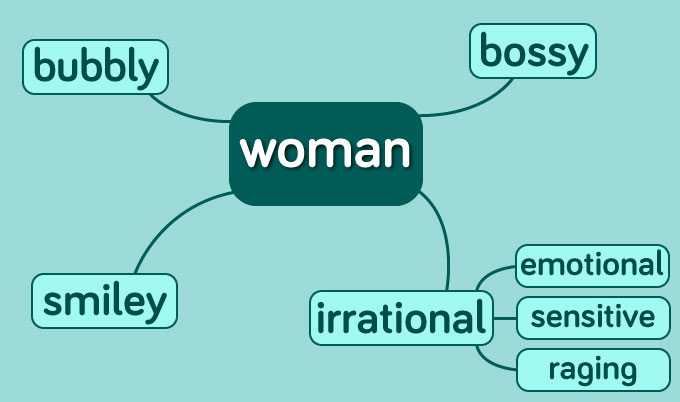

Here is a list of adjectives suggested by respondents. They might seem innocuous when considered separately. But when brought together, a picture starts to emerge, and the process of stereotyping involved becomes clearer. As shown here, gender can also be revealed as implicitly present if you consider words within their social context. Doctor, lawyer or scientist are often implicitly interpreted as masculine. This bias is reinforced by the fact that a lot of men are in such professions. Conversely, nouns such as nurse, secretary or prostitute lean towards the feminine.

- Woman

- bubbly

- smiley

- bossy

- irrational

- emotional

- sensitive

- raging

Look at these words. Ask yourself:

- Would I use it to describe a man? If so, would it mean the same thing? For example, bossy, bubbly, raging, irrational, emotional

- Do I ascribe certain traits to all members of a gender group? For example, sensitive

- Do I hold different assumptions and expectations according to gender? Do I tend to enforce them on people, for example by asking them to be more smiley? How might this affect my relationships with people around me?

- Are there gender-neutral equivalents for these terms? Would you use them?

Some gendered words are heard more about women of colour, such as feisty and sassy.

About words like bossy, a male respondent explains that they belong to:

‘the gendered language of assertion. […] It’s a way to describe (usually pejoratively) the behaviour of women, amongst men, and by men. And this is a kind of pernicious use of language, as a way of calling men into relation with each other, even when they’re uncomfortable with it, and a joint reestablishment of their control and status through the diminishment of that woman.’