Gender in so many words

Ten key notions to understand gender.

Cisgender

- Cisgender is a gender identity, understood as the opposite of transgender.

- You are cisgender if you identify with the gender assigned to you at birth.

- Being cisgender comes with social privilege. That's even for people who are socially disadvantaged in other ways.

Cisgender forms a pair with transgender. The prefix trans- suggests the idea of crossing a border, ‘on the other side of’. Its antonym cis- is about sameness, ‘on this side of’. Cisgender is alignment of an individual’s gender identity to that assigned at birth. This is very much ‘It’s a girl!’, ‘It’s a boy!’.

Trans activists created this pair of terms to highlight the norm, the default, which doesn’t need to be said. This is a way to break away from discourses about:

- deviance

- abnormality

- mental illness

The term transsexual arose from medical discourses to characterise. Doctors didn't feel the need to name all those who were not ‘transsexual’, or transgender, as we would today. That is because they separated ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ behaviour. They did not feel the need to further describe this normalcy.

Being cisgender is still considered as the implicit norm. It's a statistical one, but also one that is value-ridden. Not being cisgender is implicitly viewed by society as an unacceptable transgression.

For most cisgender people, gender identity is not an issue for them. So we can compare being cisgender to being heterosexual or white.

Living within implicit gendered and racial norms means you don’t face realities. It's a society that places more value in masculinity and whiteness. Seeing yourself as cisgender, heterosexual and/or white means coming to terms with privilege.

Gender

- Gender and sex are distinct but often conflated.

- Gender is a system of division (between women and women) and power (for men over women).

- Gender is a social construct. It's created and accepted by a society, and varies from society to society.

- Gender shapes norms and values. It influences our ideas and behaviours, even when we are not aware of it.

- Gender links to sexuality, and to assumptions about sexuality. It's assumed that men are sexually attracted to women, and women attracted to men.

The word and the idea of gender has completely permeated everyday language. It's within common thinking more generally. As recently as 40 or 50 years ago, this was not the case at all.

Where we say gender today, people used to say sex. The latter has become so omnipresent that it tends to replace the former. It has become very common, for instance, to talk of a pet’s gender, male or female.

This is how English has evolved. Distinctions between sex and gender tend to get lost in everyday language. It is important, nonetheless, to understand why they were originally two distinct concepts.

Origins in language

The successful word/idea of gender comes from feminist sociological literature. The literature borrowed and modified it from 1950s and 1960s US medical literature. In its first definitions, gender meant to be the cultural counterpart of sex.

It was a social construct, a system dividing humanity into two groups, men and women. So gender was a normative system dividing humanity between men and women.

It is set along the lines of what is a strict sexual division between male and female. This system is not only binary and intolerant of any transgression.

It is also hierarchical. The groups ‘men’ and ‘women’ are not symmetrical. The first has held, and continues to hold, power, and exert its domination over the second.

The workings of gender in everyday life are sometimes subtle. For the most part, we are not aware or them. Gender comes with a territory, defined and watertight. Men do this, women do that. Girls behave in a certain way and like certain things, supposedly different from boys.

Assumptions around gender

We reinforce these restrictive concepts of gender in a variety of ways. Pop culture, advertisements and women’s magazines are among the most codified examples. Gender thus creates a set of assumptions and instructions. They remain invisible when unproblematic. But they can lead to serious issues, and even violence, when people try to do away with them.

Common assumptions about gender can be a problem, for instance, in the workplace. One respondent describes having to be on guard to follow social expectations:

‘Do I need to speak in a particularly gendered way to avoid problems? Do I need to make sure that I don’t speak in a way that is wrongly gendered? Don’t be too much: too masculine, or don’t be too feminine. Be a bit more feminine because that makes people feel less threatened. But also, like you’re probably not saying anything important. That is a big part of how I have to think about things, and I, you know, we consciously strategise about [it].’

Identities are complex and changing

Our identities are, of course, never fixed nor only about gender. They are complex and changing. In the film Pride, a group of lesbian and gay activists raise money for the Welsh miners during the 1984 strike. Two seemingly alien worlds are thus brought together:

- by the common experience of marginalisation and police harassment

- because of social class and/or because of sexuality

As Tom Cruise gets older, his on-screen love interests remain the same age. This is because of Hollywood’s deep-rooted bias against middle-aged and older women. Beyoncé’s feminism is as much about being black as it is about being a woman.

Gender, age, race, class, sexuality, (dis)ability contribute to our identities. They define our position in the world. See Intersectionality.

Contradictory conceptions of gender

It is important to realise that there are many conceptions of gender today. Some of them contradict each other. But, in everyday language, gender is very simply understood in the way sex was before it. It's the binary division of men vs women.

When people make a distinction between sex and gender, it is often to reflect the age-old distinction between nature (reformulated as ‘biology’) and culture. Look at gender studies research and you soon understand things are more complicated. But this is a tale for another day.

Taking sexuality into account

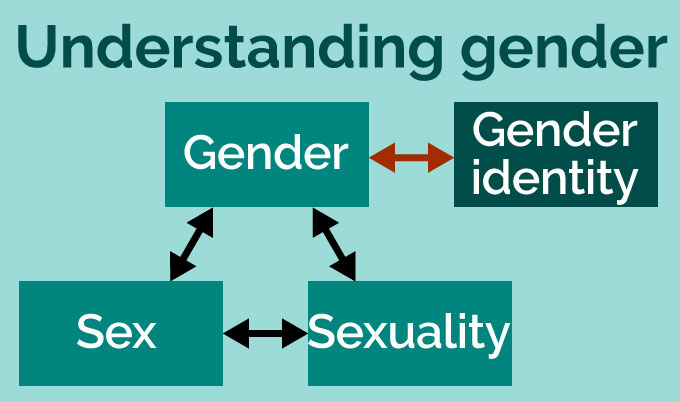

While we can't understand gender without sex, we need to take sexuality into account.

Why include sexuality in a discussion about gender? We understand sexuality as a synonym of sexual orientation. In the Oxford English Dictionary, it is ‘a person’s sexual identity in relation to the gender to which [they are] typically attracted’. There's an interlink between sexuality and gender. Assumptions about gender are also, often, assumptions about sexuality.

Transgressing norms of gender thus implies transgressing norms of sexuality. If a little boy never learns to ‘man up’, as the harmful injunction goes, does that mean he is not heterosexual? So not really a boy at all? Three distinct dimensions are often conflated in this way:

- gender

- gender identity

- sexuality

The ways we perform our gender – preferences, actions, behaviours –give rise to assumptions. These are about our gender identity (does that mean they are transgender?) or our sexuality (does that mean is she a lesbian?).

A respondent, who identifies as lesbian, explains:

‘I do feel really aware of my own gender in society. […] I don’t necessarily conform to the cisgender female […]. I’m not part of what society tries to tell we are, like, you are a man, you are a woman, you know, very confined roles within that.’

In language, we can see these links between gender and sexuality in the use of sexual slurs. A man who does not conform to social expectations about masculinity might be called a ‘faggot’. A woman who does not conform to social expectations about femininity might be called a ‘dyke’.

Whether they are gay or lesbian, such slurs punish for transgressing social norms. They are putting people back ‘in their place’, by means of verbal and/or physical violence. Slurs can seem innocuous – after all, they’re only words, right? But they carry in themselves an existential threat. One respondent, who identifies as gay, explains about the etymology of faggot:

‘... they used to burn gay, homosexual people, homosexual men. So that’s where the word faggot comes from. […] So that word is actually – it’s a word of… ‘I want you dead, almost.’

We find another way of thinking about gender more and more in everyday language. Ways in which society identifies and puts us in distinct categories, either man or woman, do not necessarily match the ways we perceive and live our own identities. We explain this in gender identity, transgender and non-binary.

Gender identity

- Gender identity sits at the junction between gender – a social system – and the ways we understand this system and build our own identities.

- Cisgender, transgender and non-binary are three examples of gender identities.

Sociological accounts of gender are all about the ways society shapes our identities. The notion of gender identity allows us to think about ways we process such expectations and constraints.

The workings of gender start as soon as the sex of a baby is identified. As most of the population fall within the female or male category, it's assumed they are either girls or boys. Society assumes we are all cisgender. Society assumes that our gender identity matches:

- our sex (male/female)

- society’s definition of gender (masculine/feminine)

But some experience a disconnect between sex, gender, and gender identity. It might be because we are not cisgender but transgender.

We were identified at birth as belonging to one gender. But our gender identity does not match these early assumptions. This is the ‘T’ in the acronym LGBTQ+.

For explanations about the ‘Q’, see queer. The other letters stand for sexualities, not gender identities: lesbian, gay, bisexual.

Some people identify as non-binary. This is a way to say their perceived gender identity falls outside of binary divisions. They are between cisgender or transgender women and men.

Intersectionality

- Intersectionality arises from the struggles of black and Latina women in the US.

- Intersection describes ways different aspects of our complex identities interact with each other. For example, the experiences of heterosexual and lesbian women, are distinct. Sexism takes a specific form for lesbian women, who also have to deal with homophobia.

- It is a useful concept to understand how different social dynamics can define and affect experiences. It is also a powerful concept for activism.

- The theory of intersectionality has been criticised as being too academic. It' said that it privileges identity politics over those struggles we have in common.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law scholar and a woman of colour, put forward this important concept. Our Dean for Social Justice, Professor Peter Hopkins, commissioned a video about it.

Masculine used as a generic

He, man, mankind…

- Using masculine forms, such as he, man and mankind, is traditionally accepted as a way to talk about all individuals, not just men. In other words, masculine is supposed to be able to act in a gender-neutral way.

- But evidence shows that speakers understand these forms more as masculine than as gender-neutral.

- It is important to consider using truly gender-neutral forms instead, such as singular they instead of he, or humanity instead of mankind.

The word ‘generic’ is used in linguistics to refer to an entire class of individuals rather than specific members. The statement Cars are bad for the environment, for instance, refers to all cars, and not specific ones: cars is thus generic.

The word man has a ‘generic use’: it can refer to any human being, regardless of their gender. When someone wants to refer to people without naming them, or to suggest a hypothetical male or female figure, ‘man’ can refer both to specific individuals within the species (males) and to the entire species (humanity).

But linguists have long been aware that this supposed generic meaning does not translate into reality. Psycholinguists, in particular, study relationships between linguistic behaviour and psychological processes. They have shown that ‘the generic potential of masculine/male expressions is a myth’ (Hellinger 2011: 570). When people hear or read masculine expressions that are supposed to have a generic meaning, they actually interpret them as masculine, as specific.

This use of the masculine as generic contributes to re-asserting what sociologists call a ‘male-identified society’, which ‘values men as a group more than women as a group’. On the other hand, consider the word womankind: it could only ever be understood as specific, as referring to women, not humanity as a whole.

Read through the phrases below. What pictures are in your mind? Do you ‘see’ men, women, or any gender? Which of the phrases are most strongly gender-specific? Are there any that truly work generically, for anyone, regardless of gender? (Adapted from Goddard and Patterson 2000: 63)

- Neanderthal man

- Man and machine in perfect harmony

- An Englishman’s home is his castle

- A gentleman’s agreement

- A man’s best friend is his dog

- The man in the street

- Man needs food, water and shelter to survive

- A small step for man, a giant leap for mankind

- If man was meant to fly he’d have been given wings

- Man overboard

- A man-made environment

- The average working man

Can the same ideas be expressed differently, without using man in a generic sense? Here are some suggestions:

The average working man : The average worker

A man-made environment : A human-made environment

Man needs food, water and shelter to survive : People need food, water and shelter to survive

The use of he to talk about people of any gender is declining but still exists. Conversely, linguists have observed a rapid expansion in the use of singular they to denote real gender-neutrality.This does not just apply to man: it concerns any masculine expression with a supposedly generic meaning.

As one respondent points out, the predominance of masculine forms used as generic depends on the domain of activity. This practice is still omnipresent in legislation and key legal concepts, for instance. We understand ‘the man on the Clapham omnibus’ to be a theoretical ordinary and reasonable person. It can be difficult to explain to students why this issue matters and why they should avoid using such forms. But it is important to highlight that gender is never neutral nor transparent. The idea that masculine forms can also serve to express genericity, while feminine forms can only refer to women, has historic and sociological roots in male domination (Bodine 1975, Spender 1980, Cameron 1998).

References

- Bodine A. Androcentrism In Prescriptive Grammar: Singular “They”, Sex-Indefinite “He” and “He or She”. Language in Society 1985, 4, 129-146.

- Cameron D, ed. The Feminist Critique of Language. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Hellinger M. Guidelines for Non-Discriminatory Language Use. In: Wodak R, Johnstone B, Kerswill P, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Sociolinguistics, London: Sage, 2011, 565-582.

- Spender D. Man Made Language. London: Routledge, 1980.

Non-binary

- Non-binary is a gender identity.

- It is used by individuals who do not identify as either women or men.

- It is also an umbrella term for many different gender identities.

The (now defunct) Equality Challenge Unit proposed this helpful definition:

‘Non-binary is used to refer to a person who has a gender identity which is in between or beyond the two categories “man” and “woman”, fluctuates between “man” and “woman”, or who has no gender, either permanently or some of the time.

‘People who are non-binary may have gender identities that fluctuate (genderfluid), they may identify as having more than one gender depending on the context (eg bigender or pangender), feel that they have no gender (eg agender, non-gendered), or they may identify gender differently (eg third gender, genderqueer).’

All these names reflect people’s need to characterise their gender identity, when this identity is at odds with the binary definition of gender – a system which imposes a strict division between feminine and masculine.

One respondent explains:

‘I just don’t feel attached to gender at all. I just feel that I’m existing outside that spectrum.’

Genderqueer, gender non-binary, genderfluid…

This variety of names, which all fall under the category of non-binary, can seem daunting at first to someone who is new to exploring gender identity. You don’t need to know all of them. But you need to appreciate that gender identity cannot simply be understood as either/or. You need to be attentive to how people refer to themselves. This binary vision of gender identity is rooted in Western culture. It not does not apply, for instance, to hijras in India or two-spirit Native Americans.

A majority of non-binary people consider themselves as transgender, but not all of them. This is why, throughout this glossary, we use the expression transgender and/or non-binary. For example, trans men would usually use masculine pronouns, and trans women feminine pronouns. But people who identify as non-binary usually prefer non-binary pronouns, such as they/them/their.

Although non-binary and genderqueer are not strictly the same, they are often used interchangeably.

Resources

Queer

- Queer used to be a slur used against non-heterosexual people.

- It can still be used as a slur today, but a lot of younger LGBTQ+ people have reclaimed it, using it proudly to identify themselves.

- It is often used nowadays as an umbrella term for people living outside heterosexual and cisgender norms.

Used as an adjective, queer originally meant ‘strange’, ‘peculiar’ or ‘suspicious’. This usage is now outdated in most varieties of English.

In the 19th century, the word started to be used as a derogatory noun in colloquial English to talk about homosexual people, especially homosexual men. Although it can remain a slur today, since the 1980s, LGBTQ+ people have used it as either a neutral or a positive. The LGBTQ+ community is sometimes called today ‘the queer community’.

The process of reclaiming the word is linked to the history of this community, in particular with the HIV-AIDS crisis. During this period, homophobia ran high. Here is how the writer Cara Ciaimo, quoting the manifesto of the group Queer Nation, explains why they chose this name:

‘[Its founders] were angry. They called themselves “militants,” “outraged,” “full of “ragged laughs that sound more demonic than joyous.” They needed a name to match their nature, and what better way to shock people than to pepper all your flyers and chants with “the most popular vernacular term of abuse” generally used against you?’

Another reason to reclaim the word was to purge it of its homophobic, harmful intent:

‘[By] co-opting the word, the group hoped to take it out of the hands of homophobes and bashers, linguistically disarming the enemy while constantly reminding themselves of what they were up against — “queer can be a rough word,” an early manifesto put it, “but it is also a sly and ironic weapon.”’

Reclaiming queer was also a reaction against the categories of ‘lesbian’ and ‘gay’. According to some, these terms impose ‘restrictive limits of gender and sexuality’. Describing themselves as queer was a rebellious, deeply political gesture. The queer community welcomed a multiplicity of sexualities and genders, and refused to conform to normalcy.

Some 30 years later, queer is often used as an umbrella term, embracing all those who live outside the heterosexual, cisgender norm. It can thus be used both about sexuality (sexual orientation) and gender identity. The acronym LGBTQ+ includes the Q of queer, while the sign + means that other sexualities and identities may be included without necessarily being named.

According to one respondent, the term queer:

‘…can basically refer to anyone on the LGBTQ spectrum, if they’re happy with that. […] I think it’s a very good term to explain the complexity of LGBTQ, because people don’t just sort of fit into a binary. […] I think it can be quite a uniting term as well.’

Resources

- A thorough history of the word in two parts, by Cara Ciaimo: Part 1, Part 2

- Queer: an episode of the excellent podcast by The Allusionist, with lots more links at the end

- Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Julia Scheele

They and other pronouns

- Some people don’t have to think about the pronouns used to refer to them. If you are a cisgender woman, people use she/her/hers when talking about you; if you are a cisgender man, people use he/his/his.

- Pronouns can become an issue for transgender and/or non-binary people, if they have to constantly announce which pronouns are appropriate for them, and to remind people of it.

- In recent years, there has been a steady rise in the use of singular they by and about non-binary people.

- Intentionally using the wrong pronouns is a form of everyday transphobia.

A common misperception holds that using they to refer to a single person is a very recent practice which originated in LGBTQ+ circles. In reality, it has long been used to refer to someone without specifying their gender, or when gender is unknown. See masculine used as generic. This is despite many, and even legislative, attempts, to impose he as the only generic pronoun (Bodine 1998).

The following example is indeed acceptable, despite what traditional grammar says:

You had a call today at 3pm. The caller didn’t give their number.

The plural they/them/their is coupled in this sentence with the singular noun caller. Speakers often use this association between plural pronoun and singular subject, especially in oral speech. The meaning of such a sentence is recognisable. It has long existed in colloquial English. If speakers have had regular exposure to it, they can recognise and understand it all the more easily (Ackerman 2018).

Things become more complicated when they/them/their refers to a specific individual who chooses to use such pronouns instead of male or female ones, rather than to provide unknown or irrelevant gender information. they is increasingly used by people who identify as non-binary, whose gender identity does not fall within the binary division woman/man. Although this novel use of the pronoun is still not universally known, Bradley et al. (2019) have shown that people can fairly easily recognise what it means.

Some trans and/or non-binary people use other pronouns, such as ze (pronounced ‘zee’)/zim/zir. A lot of creativity is possible here. It is impossible to know, let alone assume, what forms non-binary pronouns may take.

A non-binary person declaring their pronouns to be they/them/their is declaring their gender identity to the person they are speaking with. This can be a daunting perspective. It can be an issue of safety, since coming out as non-binary and/or trans can still expose someone to various forms of violence.

For cisgender people, pronouns are a non-issue. People usually get it right, and mistakes, although uncomfortable, are easy to correct. It is not something they have to worry about. For non-binary and/or trans people, it can be a repeated struggle. Their gender might not be immediately clear from their appearance, as it is for cisgender people. When the wrong pronouns are used, it is not just a mistake that creates mild discomfort on both sides. It is misgendering, and it can be a painful reminder that society does not recognise you for who you are. It might be a mistake, or it might be used intentionally to cause harm by denying someone’s gendered identity.

A postgraduate student who identifies as non-binary, talks about some negative experiences in their School:

‘Sometimes, if I’m out about the fact that I’m non-binary and I like the they/them pronouns, people aren’t very responsive to it, like kind of consistently misgender me, with she and her.’

Another respondent draws a distinction between intentional and accidental misgendering:

‘One of the people that I worked with would constantly get misgendered because she was trans. And it was a deliberate act, to misgender her. So that was bullying. I’ve also met people who are non-binary [who] would get misgendered by accident. […] Often when they get misgendered it’s not coming from an aggressive place, it’s just that people don’t understand.’

One way to make disclosing pronouns easier is to turn it into something as many people as possible do. You can, for instance, list your pronouns in your email signature. If cisgender people start doing this, it could normalise the process of sharing pronouns. It could create a safer environment for everyone.

Kirby Conrod, a linguist and non-binary person, proposes four steps for anyone to follow to make potential trans and/or non-binary people around you feel safer and included. This advice can be useful for teachers, for instance, or for anyone in a position of authority who wishes to create an inclusive space.

- Make pronoun sharing an option, but don’t force anyone to do it

- Give people more than one chance to share pronouns, and ideally set up a channel that won’t make people feel anxious

- People in authority are responsible for establishing the politeness norms in any setting (classroom or company)

- Pronouns are one of many other norms of politeness, and being explicit about your expectations saves people from trying to read your mind about that stuff

Let’s imagine a situation where someone you know has transitioned, they have started living in a way that matches their gender identity. This person now prefers to use different pronouns. When you are used to associating a set of pronouns to a person without thinking about it, it is not easy to get it consistently right. But remember: whatever difficulties you may be encountering using someone’s preferred pronouns, it does not compare at all to the difficulties of having your gender identity not recognised by the people around you.

Here are some other tips to avoid misgendering.

- If you are not sure of someone’s preferred pronouns, start by avoiding using any to refer to that person. If you have friends or colleagues in common, try asking one of those people if they know what pronouns to use. If you are getting to know this person, try asking them directly.

- Make a little bit of time to practice. If you are alone somewhere, picture them in your mind, and say a sentence referring to them correctly out loud. Refer to them in your head from time to time as you walk from one place to another. It will get easier.

- If your brain perceives your friend to be a different gender than they’ve told you, work on changing that perception for your particular friend. Imagine them as you know them, and focus on the ways they express their true gender identity. Give your brain new cues to latch onto.

- You will get it wrong at first. When you do, correct yourself immediately, and don’t draw any further attention to it. For example, ‘That pineapple is hers. His.’, ‘I love his sweater! I mean her sweater – I love her sweater!’, ‘He – they – wanted a doughnut, so I got one for them.’

- Be patient with yourself, and with your trans friend. Pronouns are hard. This stuff is hard. Hang in there. If you’re genuinely trying, then we’re on the same team.

References

Ackerman, LM. Our Words Matter: Acceptability, Grammaticality, and Ethics of Research on Singular 'they'-type Pronouns. 2018 (pre-print), PsyArXiv [online], DOI: psyarxiv.com/7nqya/download?format=pdf

Titles: Miss, Ms, Mrs, Mx, Mr, Prof, Dr…

- There are significant disparities in the use of titles for men and women.

- For women, having to choose between Miss and Mrs means having to declare your marital status.

- Ms is increasingly used as a third option and comes with its own connotations.

- The academic titles Dr and Professor are not supposed to be gendered, but are still implicitly associated with men.

A title is a word used before someone’s name to denote their status or profession, or role within an organisation.

When required to give their title, women may choose between three options. Miss denotes that someone is young and/or unmarried. Mrs is only used for married women. But boys and men are not required to divulge their marital status nor their age. Unless they have another title due to their status or profession, they are all called Mr.

A third option is available to women, Ms (normally pronounced /ˈmɪz/, but also /məz/ or /məs/). Reintroduced by feminists in the 1960s and 70s, it originated in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is only in the 19th century that women began to be strictly defined as either married or unmarried. The idea behind the reintroduction of Ms in the late 20th century was to avoid women being defined by their relation to a man. It was supposed to replace the Miss/Mrs alternative.

But today, Ms appears not as a unique option but as yet another one. Although it is well-known, it has not eradicated the distinction between married and unmarried. It has gained new connotations, such as ‘divorced’, ‘feminist’ and ‘lesbian’ (Hellinger 2011). Anecdotal evidence suggests that young women in the UK seem either unaware that using Ms is an option for them, or reticent to use it. This may be because of such connotations.

Another, less well-known title is Mx (usually pronounced /mɪks/ MIKS or /mʌks/ MUKS and sometimes /ɛmˈɛks/ em-EKS). It does not indicate gender and can be used as an alternative to gendered pronouns. It is now widely accepted in the UK, but does not figure as an option on all forms.

Women are constantly reminded of their gender by having to choose between at least three titles. For non-binary people, it is another reminder that they don’t fit within the boundaries set up by society around gender. A respondent explains that, while filling out applications, having to pick a title was an issue:

‘I don’t feel like I can put [a gender-neutral title] on the form, even though that’s what I’d rather have. […] That would be the first thing they read. […] That is going to affect what they think about me, when the whole equality, diversity bit is supposed to be anonymous.’

In an academic context, two other titles are often encountered: Dr (Doctor) and Prof (Professor). As opposed to the ones above, they have no gender connotation, or at least they are not supposed to. The title of doctor is acquired by achieving a Doctorate. The title of Prof is conferred in the UK and most Commonwealth countries to senior academic staff who hold a ‘Chair’.

While Dr and Prof are not supposed to be gendered, they actually carry implicit male connotations, as with most positions of prestige. This has to do with the process of mental imagery, as described in masculine used as generic. A respondent recalls, for instance, a Law paper in which the client was a woman and a Doctor. A lot of students read the situation too quickly and talked about the client as ‘he’. Many women in academia have had the experience of students using any title but ‘Dr’ or Prof’ to address them.

This is rarely an intentional gesture. It is almost always based in largely-shared gender assumptions and/or ignorance about titles in a university context. This is why it is important, in particular, to explain to students how to use such titles, and why it matters.

Transgender

- Transgender is a gender identity.

- Being cisgender means identifying with the gender assigned to you at birth. Being transgender means identifying with another gender.

- Transgender people are increasingly visible in the media, which can help inform people about what it means to be trans. But not all these representations are positive, and a lot of them perpetuate transphobia.

- Transphobia can manifest itself in many ways, from intentionally using the wrong name and pronouns for a trans person to physical violence.

A pair of words is actually at stake here. To understand what transgender means, we need to understand cisgender. While the prefix trans- suggests the idea of crossing a border, ‘on the other side of’, its antonym cis- is about sameness, ‘on this side of’. Cisgender or being cis describes the alignment of an individual’s gender identity with the sex they were assigned at birth (“It’s a girl!”, “It’s a boy!”).

We live in a society where the default human being is still assumed to be heterosexual and cisgender, not to mention male and white. See gender identity, masculine used as generic, intersectionality. We know that not everyone is cisgender. But gender is fundamental to the way we see the world and other people. This can make it difficult for some to go beyond this assumption, to see and accept the reality: gender identities are diverse and complex.

You might accept this as a hypothetical scenario, and think that you have never met a trans person. But it is possible that you have, without knowing it. Not all trans people are visibly and/or openly so.

Laverne Cox’s part in Orange is the New Black has marked a new era of increasing presence of trans actors and/or characters on screen. Chelsea Manning and Caitlyn Jenner’s very public transitions also played a major role in raising public awareness around trans identities. But if trans issues are more in the spotlight, it is not necessarily in a good way. A large section of the UK‘s popular media is violently transphobic. It regularly sets out to present trans people as other, deviant, and threatening.

Since 2014, hate crimes committed against gay, lesbian and bisexual people have doubled. Hate crimes against trans people have trebled. According to The Guardian, almost half of all transphobic crimes reported to the police in 2017-2018 were violent offences, ‘ranging from common assault to grievous bodily harm’. Trans women of colour are particularly at risk.

Throughout this glossary, we use to word transgender and its shorter version trans + noun (trans people, trans woman…). This is the word used by trans people today to describe themselves. Some other terms are likely to cause offence.

Terms likely to offend

Transsexual comes from psychiatry. It is a remnant of the extremely recent past, when being trans was considered as a mental health condition.

The slur tranny is by definition meant to cause offence. It falls under verbal violence, unless a person uses it to describe themselves, in which case the word is being reclaimed.

Cross-dressing is often conflated with transgender, but should be kept distinct. The practice is often associated with heterosexual men who like wearing ‘women’s clothing’, as defined by society. Sometimes they find it relaxing. Sometimes it is because it suits their personality more. Sometimes they are not heterosexual men, but transgender women, exploring different ways of presenting themselves. Cross-dressing has nothing to do with sexuality, and everything to do instead with gender expression.

Transvestite is usually considered inappropriate for both cross-dressers and trans people.

Resources

- 50 Years Married to a Man Named Sissy: an episode of the podcast Death, Sex and Money about a cisgender, heterosexual cross-dressing man

- Mermaids: UK charity campaigning for the recognition of gender dysphoria in young people and call for improvements in professional service

Transgender guidance from the Independent Press Standards Organisation: guidance for journalists on how to cover issues related to trans people

I got it wrong. What do I do?

Thinking and talking about gender requires nuance and adaptability. Here are some recommendations.

- First and foremost, consider it possible that you might be wrong.

- Take the time to listen to and learn from people who experience things differently, because of their gender, their race, their social background…

- If someone points out you have made a mistake, pause, listen, and if necessary correct it. It’s possible you might have caused offence; if so, apologise and move on. No need to dwell on it.

- After the incident, learn more about your mistake – not necessarily from the other person involved! You can start with this resource, or one of the many others indicated here.