Middle Leadership Blog Series Case Study Post 2

How to transform learning in your context

Who is this blog post for: Current or emerging middle leaders and for senior leaders or Headteachers who are developing middle leaders.

Author: Stephanie Bingham

Posted on: 14th November 2023

Keywords: Change; Prepare; Plan; Explore; Implementation; Enabling.

Introduction

Throughout this series we have explored the transferrable skills of teachers and their application to leadership. In our most recent posts we have focused on implementation, examining the complexities and common pitfalls, and presenting some implementation models which help leaders to manage change successfully. We have also, in practice post 1, shown how leaders can create a culture of learning within their team, focusing on how meetings can be more effective if they have a learning intention and the leader has created a culture of collaboration and joint setting of norms.

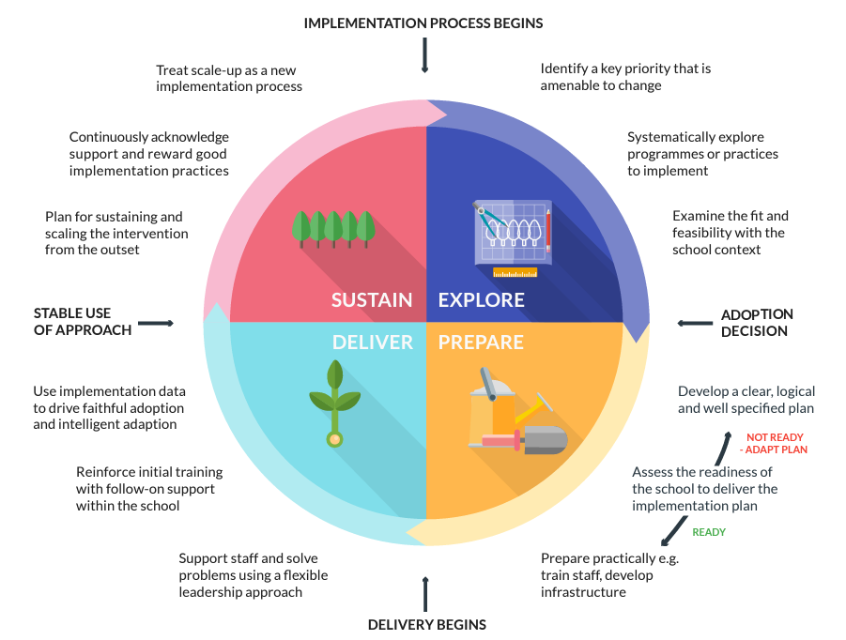

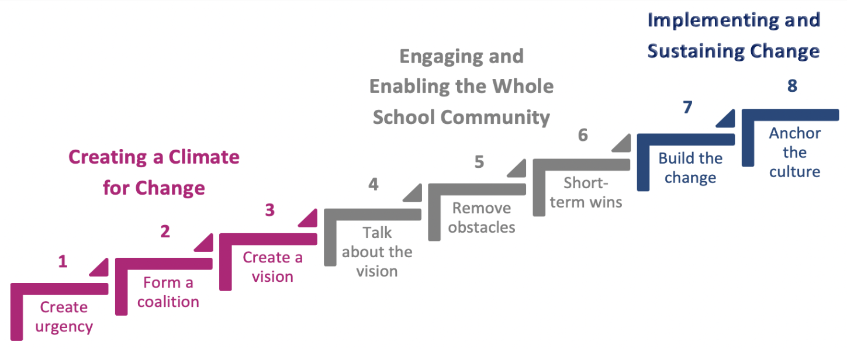

This case study draws all of these themes together through a real example of implementing curriculum change to improve pupil outcomes. The leader’s actions reflect the recommendations of the EEF Implementation Guidance (2021) and Kotter’s 8 Steps for Change (2012), as shown in the figures below, respectively.

| As you read, think about how you can transfer the learning to your own context when planning for change. |

Case Study

The teacher in this case study works in a Primary School serving a community with below average levels of deprivation. They are the leader of Modern Foreign Languages (MFL), and their change initiative aimed to improve the progress of disadvantaged pupils (DP) in upper Key Stage 2 (KS2) French and narrow the performance gap between them and their non-disadvantaged peers. The leader also sought to improve the practice of their non-specialist teachers and trainees. This first extract illustrates how they prepared for their change through exploring a variety of evidence:

Extract 1

|

Since I joined the school, there has always been an attainment gap between DP and non-DP pupils…... I observed that [in French] there was also a gap between male and female pupils, which led me to researching different strategies that could be used to improve standards and increase engagement in French. I extensively researched into digital learning given that the evidence of the impact of this was very strong; however, the costs meant that this wasn’t possible. The purpose of learning a language is to communicate so I looked into Collaborative Learning (CL). This was supported as an interest by pupils during their initial pupil voice survey. Over 60% of pupils expressed a desire to work in groups. CL is something that I had experienced in a previous school and I knew the benefits that it could provide. Furthermore, “students who learn in small groups generally demonstrate greater academic achievement ... than their more traditionally taught counterparts.” (Springer et al., 1999). I also considered advice from Wang’s (2009) study that it was important for pupils to be apart from friendship groups and ultimately grouped in mixed-ability bubbles. Following this research, I was then able to include CL activities within my action plan with confidence. To allow my team and me to monitor pupils’ progress closely, it was essential that pupils took a baseline assessment. All pupils were given a starting grade, which was not shared with pupils but was for staff use only. The rationale for this was to clearly show pupil progress and highlight concepts, knowledge and skills that they already knew as well as any misconceptions that they may have already had. This was a fantastic starting point and together with a pupil voice survey we were able to monitor progress throughout the project. Each member of staff completed a self-audit. Curriculum plans were looked at and I met with teachers from other schools to ensure that our provision was satisfying the programme of study. It was agreed that the writing element of the curriculum was strong but more progress and emphasis needed to be placed on spoken French. This was supported by pupil voice, which collectively stated ‘there was too much written work’. |

Following this extensive data gathering and exploration the leader was able to identify where the intervention should be focused using a proven model. The intervention has an inbuilt tool for monitoring the progress of the pupils, and the leader had a clear idea of the strengths and areas for development for their teaching team. They outlined the initial meetings that were held and the careful work done to ensure that the team feel involved and have ownership of the initiative:

Extract 2

|

The action plan was shared with staff and the rationale was explained, including the research that I had undertaken through the EEF toolkit. I used the visionary leadership technique outlined by Goleman (see Theory Blog post here) to develop and articulate my ideas and solicit the opinions of the members of my team. The effect of this meant that my team agreed to adopt my initiative and move forward with it because they felt that they had contributed to the overall vision and pathway of the initiative. |

Note that aside from data-gathering and triangulation, which all form part of the preparation stage, no implementation has yet taken place. This reflects both Sharples’ (2021) and Kotter’s (2012) emphasis on importance of the preparatory stage of implementation planning: they have investigated the school’s readiness for the change and they have ensured that they have support from their team. This leader also had conversations with an in-school coach who helped them to think through how they would manage their team and lead the change. This is also part of the preparatory stage: planning for potential difficulties before they arise, and understanding the different members of the team and how they will be most effectively led.

Once the data had been analysed and the potential curriculum models explored, a clear implementation model was adopted, which included monitoring points, delegation of responsibility, and provision for adaptation where needed. This is what the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) Implementation process refers to as preparation (2021), and Kotter (2012) as creating a climate for change and engaging and enabling the whole school community:

Extract 3

|

To manage change, I put an action plan in place with regular checkpoints. I used the idea of Brighouse and Woods (2013, p.19) to ensure that all of the components needed were in place to support the curriculum changes. I shared my vision with my team in a formal meeting. I spoke to all staff individually to invite them to the first meeting. This was very important in order to set the scene and standards I allowed for certain aspects of the project to be discussed and I shared my lesson expectations with staff members. I also gained the trust of staff by delegating effectively to team members. I designed an expectation sheet which outlined the basic expectations of a language lesson and gave this to all team members to try and minimise in-school variation. The project was designed to use teacher assessment grades which gave us the whole picture for each pupil. Ultimately, staff felt that they had sufficient opportunities to give feedback and that their feedback was listened to. Pupil voice feedback was used to shape the project. I was able to identify risks that could have a detrimental effect on the project. I used the school’s risk management template and process in order to do this to ensure that I was able to put the correct measures in place for any risk identified………throughout the project I was able to keep check on the potential risks and update the risk register. This meant that most risks were taken into account and were mitigated. |

Extract 4

|

Meetings that I held were well-planned and well-structured to ensure my team thought that they were meaningful and productive. Pupil voice panels were very useful and gave pupils the opportunity to share their views in a comfortable and safe environment. Lesson observations and book reviews also allowed me to manage the changes. The impact of these change management techniques ensured that all staff members were aware of the plans and adapted to change effectively and without conflict. More data was collected after each assessment so that we had maximum information on each child. This worked well as all data was centralised which meant I was able to manage and analyse effectively. Pupils who were not on target received a personalised plan. For example, some pupils were given support frames to assist them with their work. In light of the data, I was able to use Teachers C and D as teaching assistants for those pupils who were not making the required progress. They held 1-2-1 sessions with those pupils to accelerate their progress. |

The impact on the pupils was maximised by the leader having built in data gathering and also plans for addressing individual pupil need. Because the data analysis included lesson observations, they were able to identify more accurately the cause and potential solutions to any problems. Pupil achievement data alone is not enough to enable staff to address pupil need.

The intervention led to 88% meeting their target outcome, thus significantly narrowing the achievement gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils in French. In order for this impact to be sustained the leader made permanent many of the actions used in the initial initiative:

Extract 5

|

As leader of the French department, I have also been able to work effectively with language departments in other schools to ensure the continuation of a consistent and outstanding provision across the school. The impact of collaborative learning was evident in classrooms. The collaborative learning strategies have been well received by pupils and there seems to be a buzz in MFL classrooms. We continue to monitor data regularly and use the methods we introduced to raise pupil achievement. I continue to use coaching with all members of my team and I delegate more tasks, something that I was often unwilling to do before. We have a bank of shared resources so that non-specialists don’t feel overwhelmed, and we continue to share successes and ideas in our weekly meetings. Staff feel confident to raise concerns and we have ongoing training to keep our lessons fresh. |

Conclusion

This case study illustrates that careful planning is at the heart of successful implementation. Both Kotter and Sharples emphasise the importance of the early stages of any initiative, and of preparing the ground before trying to implement change. Effective implementation can’t happen without being founded on strong evidence, which in turn needs to be shared with the team in such a way that they will share the vision and help to make it happen. This middle leader also understood the importance of ensuring that the change was sustained, putting in place an action plan with regular check points, and building in collaboration with other language teams to ensure the process remains live and dynamic.