Sean O'Brien on the O'Brien (Sean) Archive

Collected Voices

Sean O'Brien was born on 19 December 1952 in London, and is a British poet, critic and playwright. O'Brien's book of essays on contemporary poetry, The Deregulated Muse (Bloodaxe), was published in 1998, as was his anthology The Firebox: Poetry in Britain and Ireland after 1945 (Picador). Cousin Coat: Selected Poems 1976–2001 (Picador) was published in 2002. Sean O'Brien's new verse version of Dante's Inferno was published by Picador in October 2006.

His six collections of poetry to date have all won awards, including the Eric Gregory Award (1979), the Somerset Maugham Award (1984), the Cholmondeley Award (1988), the Forward Poetry Prize (2001 and 2007) and the T. S. Eliot Prize (2007). In 2007 he won the Northern Rock Foundation Writer's Award, Forward Prize for Best Collection and the T. S. Eliot Prize for The Drowned Book (Picador, 2007). This was the first time a poet had been awarded the Forward and the Eliot prizes in the same year. In 2006, he was appointed Professor of Creative Writing at Newcastle University, and was previously Professor of Poetry at Sheffield Hallam University. He is a Vice-President of the Poetry Society. He was co-founder of the literary magazine The Printer's Devil and contributes reviews to newspapers and magazines including The Sunday Times and The Times Literary Supplement and is a regular broadcaster on radio.

His writing for television includes 'Cousin Coat', a poem-film in Wordworks (Tyne Tees Television, 1991); 'Cantona', a poem-film in On the Line (BBC2, 1994); Strong Language, a 45-minute poem-film (Channel 4, 1997) and The Poet Who Left the Page, a profile of Simon Armitage (BBC4, 2002). Other significant work includes a radio adaptation for BBC Radio 4 of We by Yevgeny Zamyatin.

His memories of Morden Tower

Newcastle Centre for Literary Arts and the popularity of poetry readings

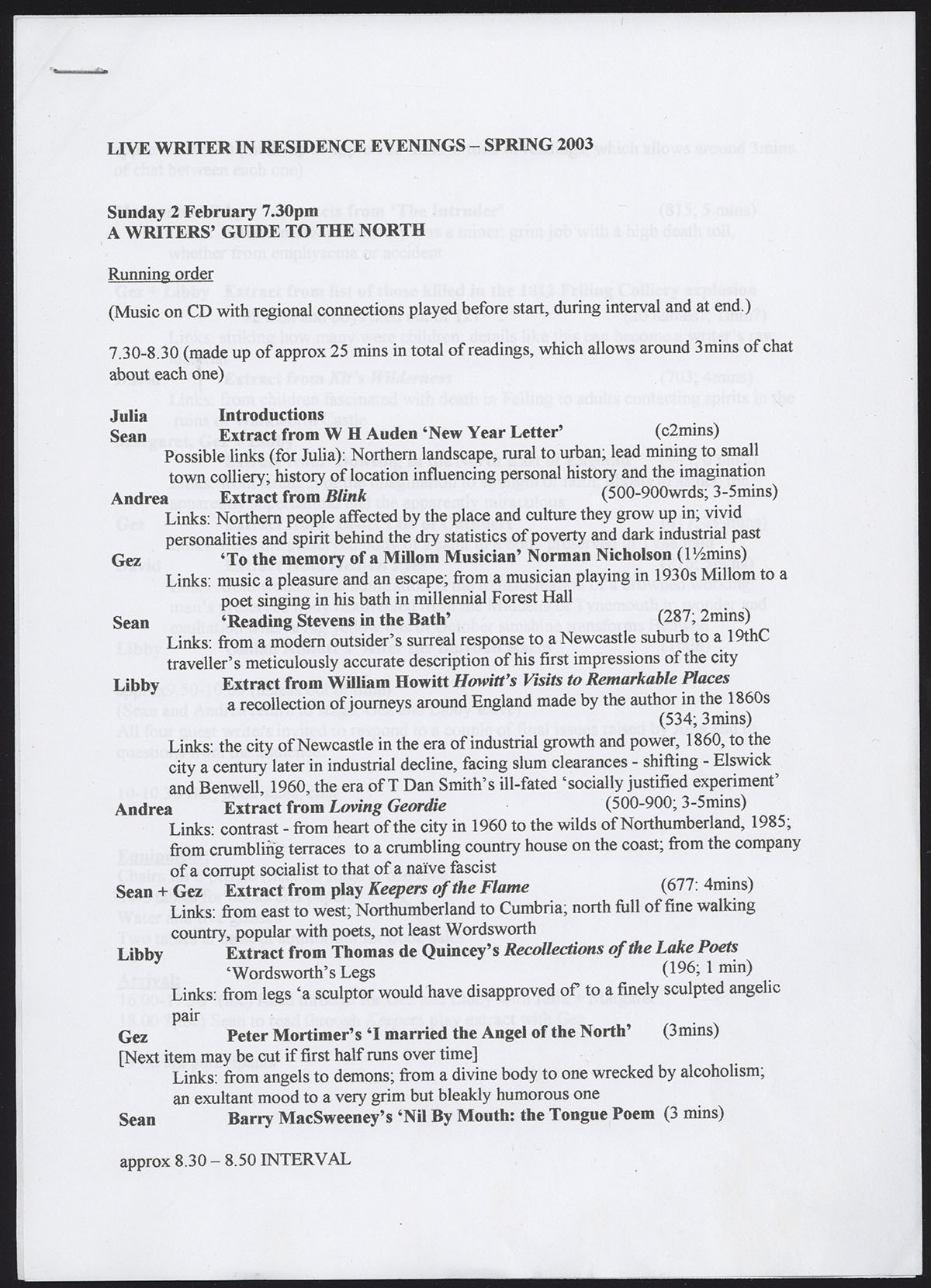

On his Live Theatre residency alongside Julia Darling

On his writing process for poetry

On publishing his first poetry book 'The Indoor Park'

On relationship with local poetry publishers Flambard Press and Iron Press

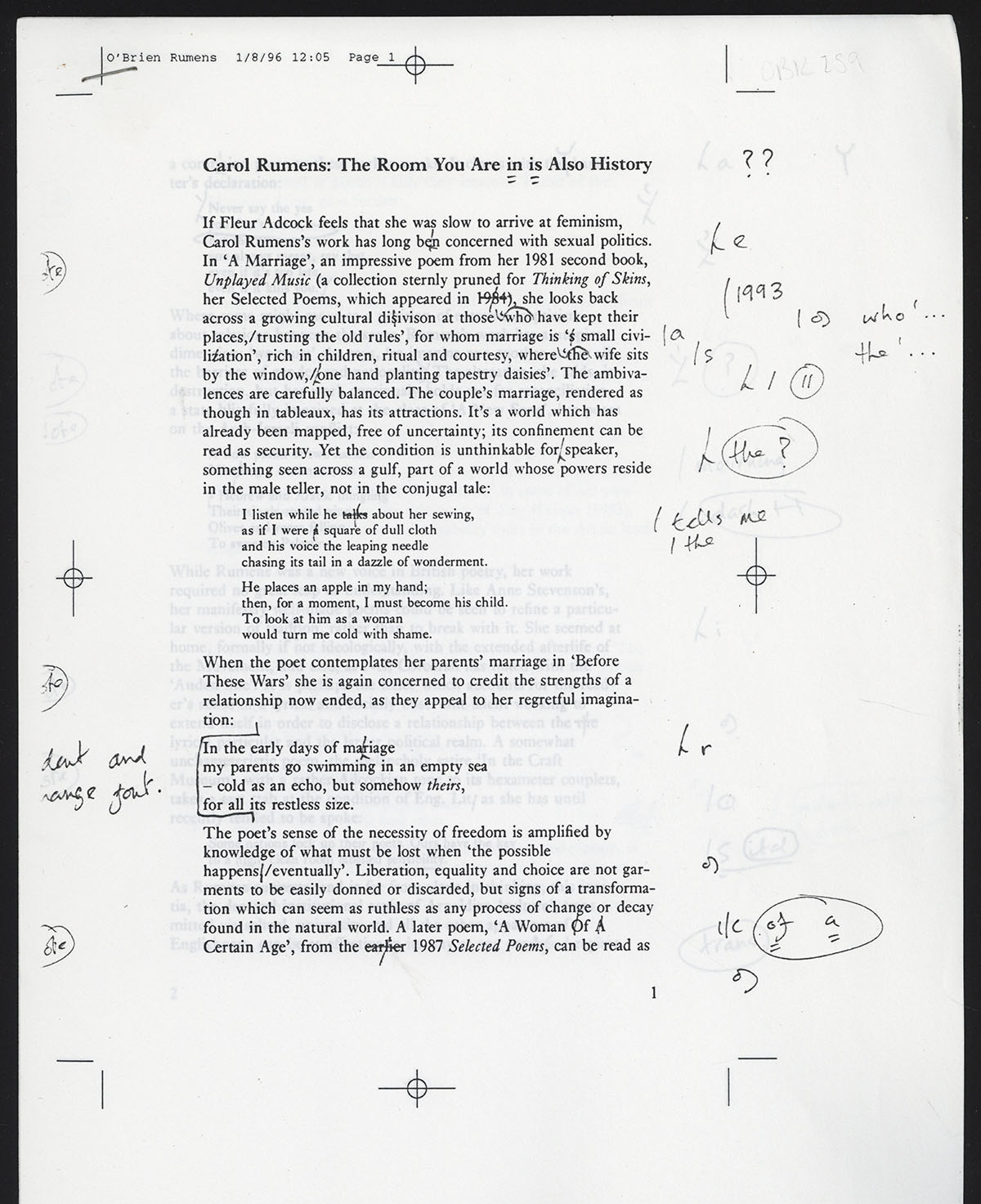

On writing fiction and the publication of Afterlife and Once Asssembled Here

On writing literary criticism

Listen to the full interview

Read the text summary

00:00: O'Brien begins by discussing when he started writing poems. At fourteen (summer of 1967), he realised almost 'overnight' that poetry was what he wanted to do. The Indoor Park, O'Brien's first poetry book was published by Bloodaxe Books in 1983 - when Bloodaxe was still quite a young outfit. O'Brien describes how this was very exciting for him, due to the difficulty in publishing books at that time. The process itself involved selecting poems from his body of work and then completing it. It was a symbolic experience for him.

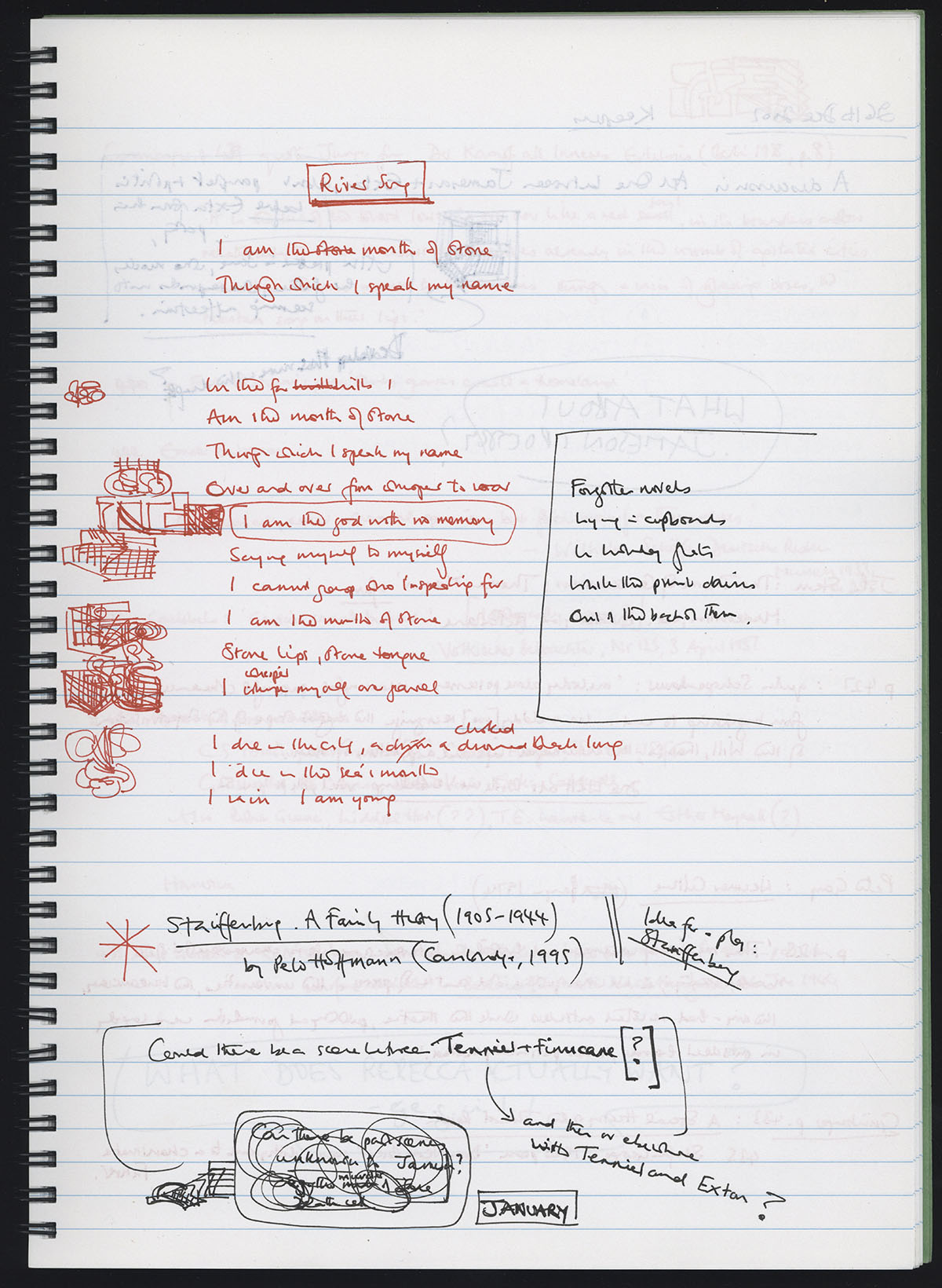

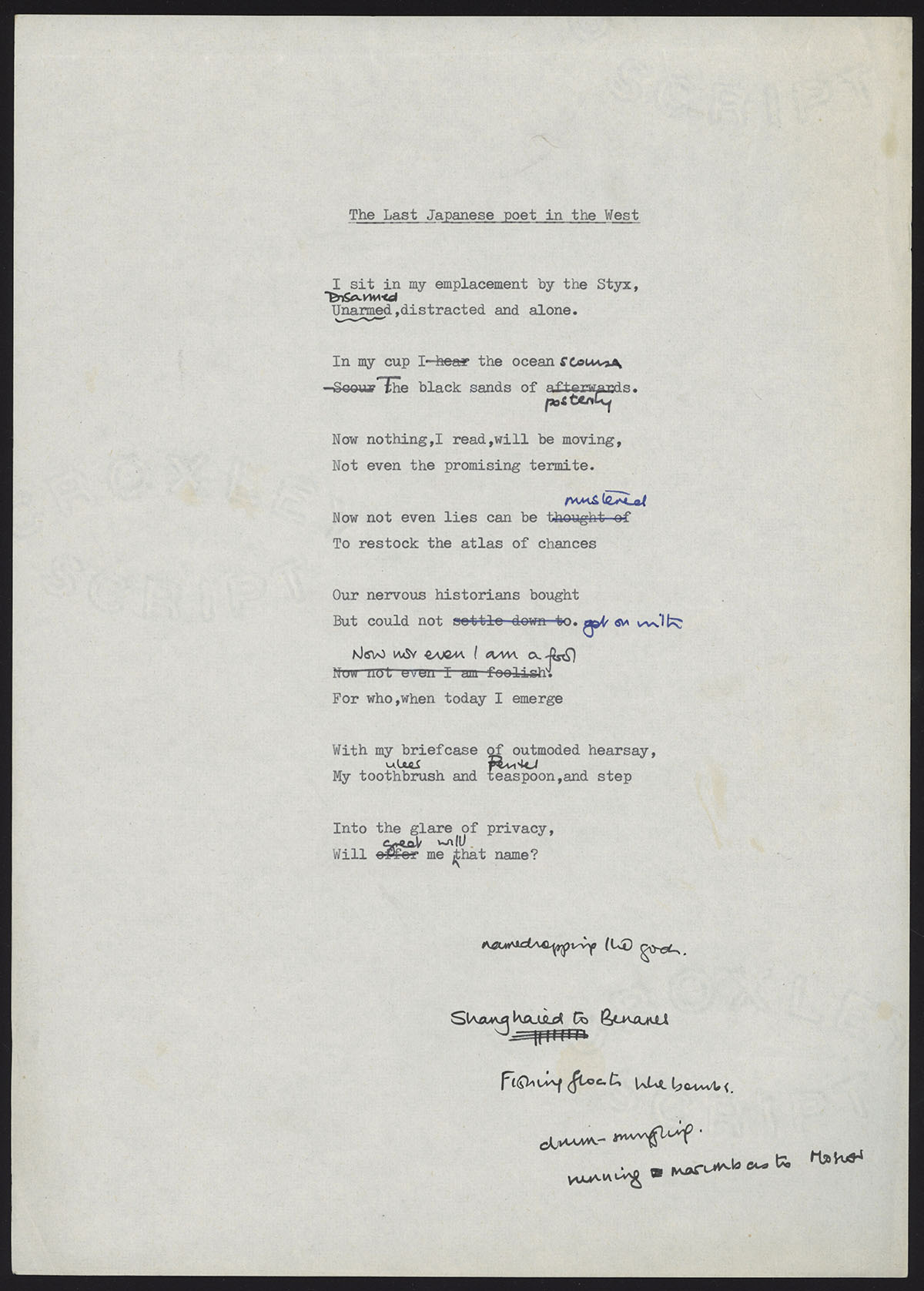

02:39: O'Brien's writing process involves writing on blank sheets of A4 paper at his desk. For him, there is something about the size and blankness of this that is appealing. He writes 'as and when ideas come to him' but he is often as his desk writing anyway; whether that is plays, reviews, songs, libretti, fiction, radio scripts etc. The poems are the most important element in this. He discusses how something can prompt you to think writing a line, or a phrase, or the shape of a sound and, if he is lucky, this can turn into something resembling a poem, which may have something to it worth persisting with. The process of writing a poem can vary for O'Brien - taking a relatively short period of time or sometimes several months. The length of time for writing a poem is not relative to the length of the poem itself. Rather, it depends on some feature that he is trying to bring into focus, a balance he is trying to create or a musical shape he is trying to discern. A great deal of revision will follow this initial process.

04:35: For the last 25 years, O'Brien has been running a monthly workshop at his house where writers exchange one another's work. This gives O'Brien, and the other poets, the opportunity to try out new material on a discerning and demanding audience. O'Brien also gradually feeds new poems into readings he does across the country.

05:15: O'Brien moves on to discuss how he went into writing fiction. He had always wanted to write fiction but hadn't been able to begin this satisfactorily. Following a request to write a short story from the short fiction publishers, 'Comma', O'Brien completed a whole book of short stories. This gave him the impetus to write a whole novel. There was a story that had been 'nagging at him' about writers of his generation who were feeling unfulfilled: artistically, romantically or politically. The story piqued the interest of O'Brien's editor at Picador who signed him up to complete this.

06:40: O'Brien states that while he finds writing poetry difficult, he finds writing fiction near impossible. Following the completion of Afterlife, he said he would never write another one, but several years later he found himself writing again. The second novel Once Again Assembled Here is about the 60's. O'Brien speaks about how he wishes to also write about the 80's so that Afterlife (set in the 70s), Once Again Assembled Here and a future book might form a trilogy; linked thematically about changes in these periods, but not character-led.

07:40: O'Brian talks about the significance of the Northern Arts Literary Fellowship. Dating back to the 60's, and beginning with Basil Bunting, The Fellowship was set up to draw the writers into the university setting, whilst also being able to focus on their own writing. His time in the Fellowship involved making contacts outside of the university - perhaps via the Northern Centre for the Literary Arts. This was often setting up workshops and building a strong, supportive literary community.

09:45: O'Brien discusses his residency at Live Theatre with Julia Darling. Max Roberts, artistic director of Live, had come across a poem of O'Brien's and asked O'Brien if he was interested in writing a play. O'Brien then wrote a verse drama called Laughter When We Are Dead, which focuses on the corruption of Labour politics during a party conference being held in Tyneside. Julia Darling, a friend of O'Brien's, was also asked to contribute and the together the two wrote several plays including, One Actors and sketches for a cabaret, organised events. O'Brien found the experience very useful.

11:07: O'Brien finds the experience working of the theatre very interesting. As a poet, you are the 'writer, producer and star' of your own work but in the theatre it is a more collaborative process.

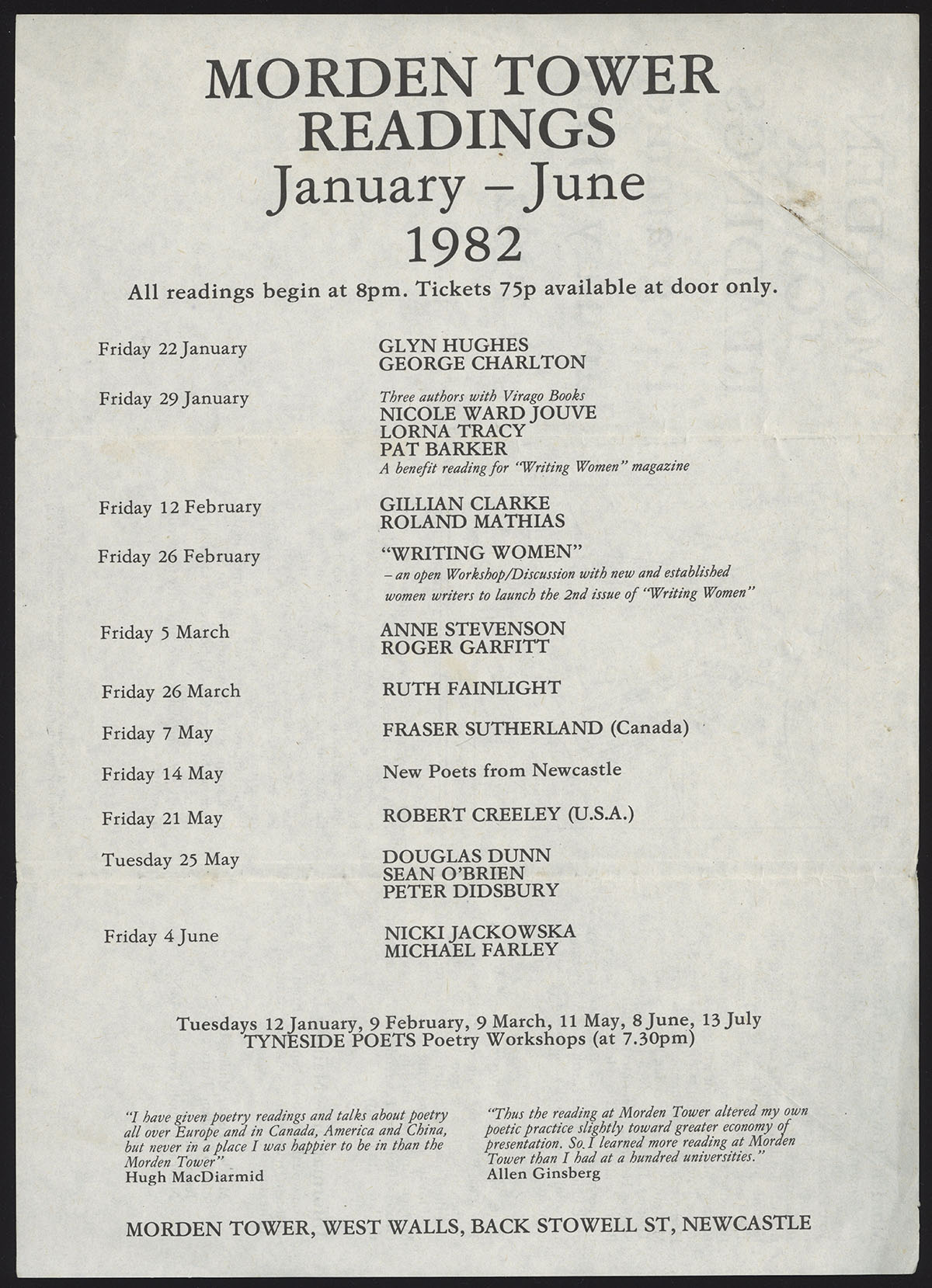

12:00: O'Brien discusses reading at Morden Tower. Prior to the release of his first book, O'Brien had a poem in A Rumoured City - an anthology of poems by poets from Hull published by Bloodaxe. He read at the Tower to promote it alongside Douglas Dunn and Peter Didsbury. O'Brien grew to like Morden Tower and after his move to Newcastle, he would regularly attend readings there - often walking out if he was unimpressed!

13:04: O'Brien recalls a reading he did shortly after moving to Newcastle and the poet Keith Armstrong 'the jingling Geordie' was in the audience. Armstrong is notorious for his opinions and shouted 'You Bloody Liar!' at O'Brien following the first line of his first poem.

13:33: O'Brien talks about the history of Morden Tower - commenting how it was very famous and attracted audiences and poets from all over the world. He laments that it is not operating as much anymore and stresses its importance as a venue for poets.

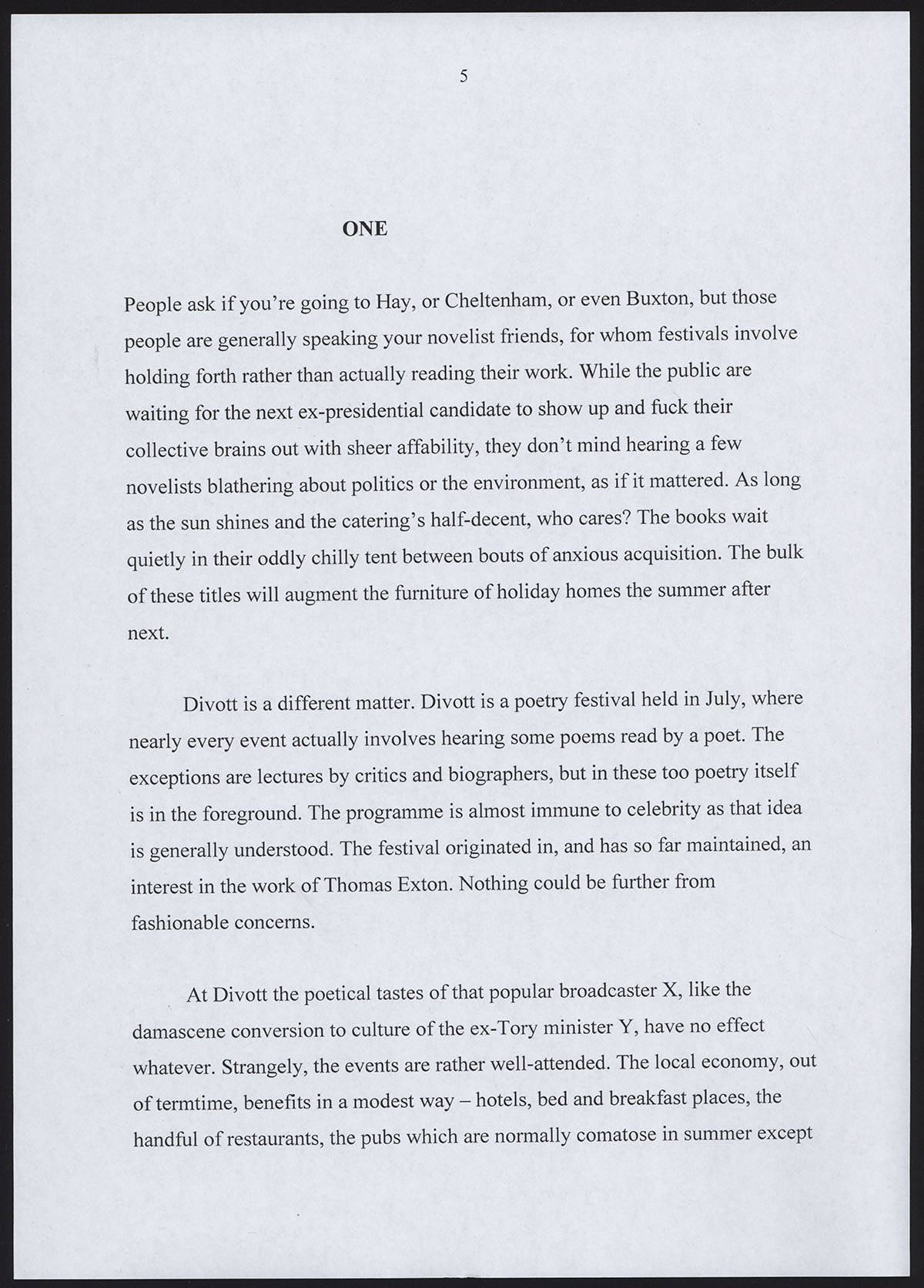

14:59: O'Brien discusses his interest in literary criticism. For him, if you are a poet, you are reading all the time and engaging with other people's work, working out their craft. This puts you into the position of a critic already: for O'Brien, criticism is an extension of the act of writing poetry for this reason. He discusses the path that literary critics take: often writing reviews in magazines such as The New Review, before moving onto TLS, London Magazine and then gradually moving into writing newspapers. For a long time, O'Brien wrote for The Sunday Times, The Guardian and The Independent.

17:00: O'Brien's relationship with Douglas Dunn. Dunn is a very distinguished poet. O'Brien and Dunn met in Hull when they both lived together. Dunn advised him on his work and O'Brien is greatly thankful to Dunn for his support as both a friend and teacher. He also discusses his friendship with Peter Porter.

18:30: O'Brien discusses winning both the T.S. Eliot and Forward Prize in the same year. He says this was very unexpected. He also won the Northern Rock Writer's prize that year. It doesn't make it any easier to write but it does give you a temporary boost of confidence that what you've been doing is worthwhile.

19:45: O'Brien feels a strong connection to the poetry scene in the North East. He feels there are some very good poets just starting to make their mark on the scene, including Chris Johnson, John Challis and Dave Spittle and others. There is a large body of distinguished writers too who have worked here for a long time. He discusses how there is a large variety of work available and it is a lively and vigorous community but there is a perception the North East as a 'world unto itself' - while it is good people can live and work here, it can be imprisoning in the sense that people are sometimes afraid to look further away in case of rejection.

21:43: O'Brien discusses depositing his archive at Newcastle University's Special Collections. He was interested that anyone should want it or that it could be of interest for study. While he retained several things for 40 years, he worked for 2-3 months ordering the material. During this time, he found several things he had forgotten about. He was surprised at the body of work and how your relationship to this changes. It is almost like amnesia. This sizeable body of work seems more or less unknown to him as it ceases to be present to you when you move onto the next thing.

24:00: O'Brien discusses co-founding the literary Magazine, The Printer's Devil. Stephen Place - playwright and librettist suggested to O'Brien there was an opportunity to start a literary magazine that would encompass poetry, short fiction, interviews etc. but also have a historical and political dimension. It would reflect their mutual interests, coalescing poetry, fiction, drama and history and politics. It ran for around ten to eleven years. The magazine was 'alphebetised' rather than numbered. They got half way through the alphabet before the Arts Council cut the funding.

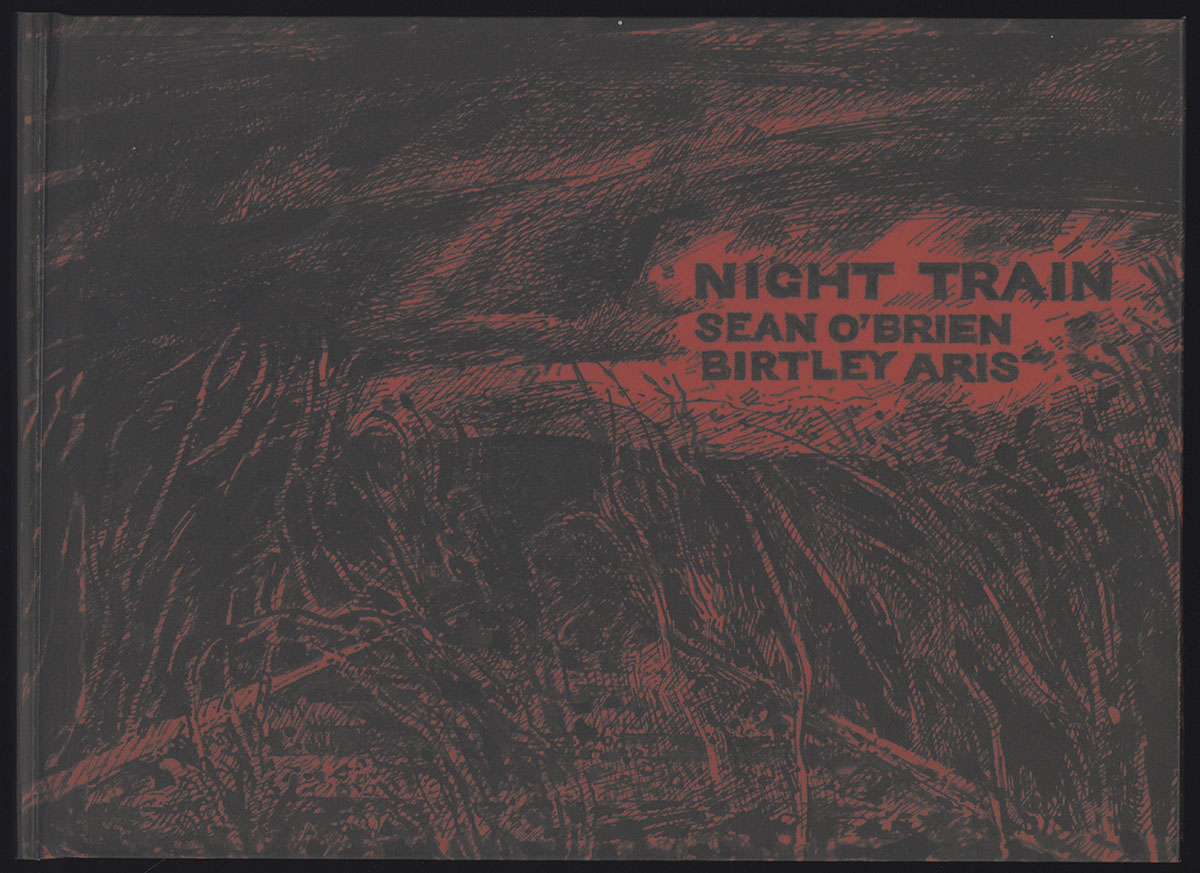

25:30: O'Brien recollects his relationships with local, independent publishers. He remembers his collaborative project, Night Train, with Birtley Aris, published by Flambard Press. It was a collaboration of drawings and poems. Flambard were supportive and the work was published successfully in hardback and paperback. O'Brien has had a lot of dealings with Peter Mortimer of Iron Press. He states that there are a lot of local, independent publishers that come and go on the scene - these are called 'Fugitive Presses' that spring up momentarily. All over the country there are small imprints that accommodate the extraordinary number of poets who want to get into print.

28:20: O'Brien deliberates that the poetry scene has changed enormously. When he first began publishing, the scene was 'a map you could take in at a glance'. These days it is much more diverse and hard to keep track of.

28:49: O'Brien claims translating poetry is a process of 'extreme anxiety'. He began by translating one or two poems by Baudelaire for his own enjoyment and included them in a book. He then translated some by Rilke, which were published in a magazine. He later agreed then to translate The Inferno. The process in this instance, was with the text, dictionary and prose commentaries. He worked with Alistair Elliott - a poet and translator - who would edit it. O'Brien's version is in English, unrhymed blank verse and chose this to allow for the steady, incandescence of Dante's work to emerge without having to deform the syntax and sentence structure to accommodate other technical demands, such as 'terza rima'. The translation took a long time and was well received. Since then, he's translated the Cape Verdian poet Corsino Fortes - who wrote in Portuguese Creole - which he worked on with translator Daniel Hahn. He has also done a couple of plays from Spanish, including Calderón's The Grand Play of the Fabulous Musician and Tirso de Molino's Don Gil of the Green Breeches.

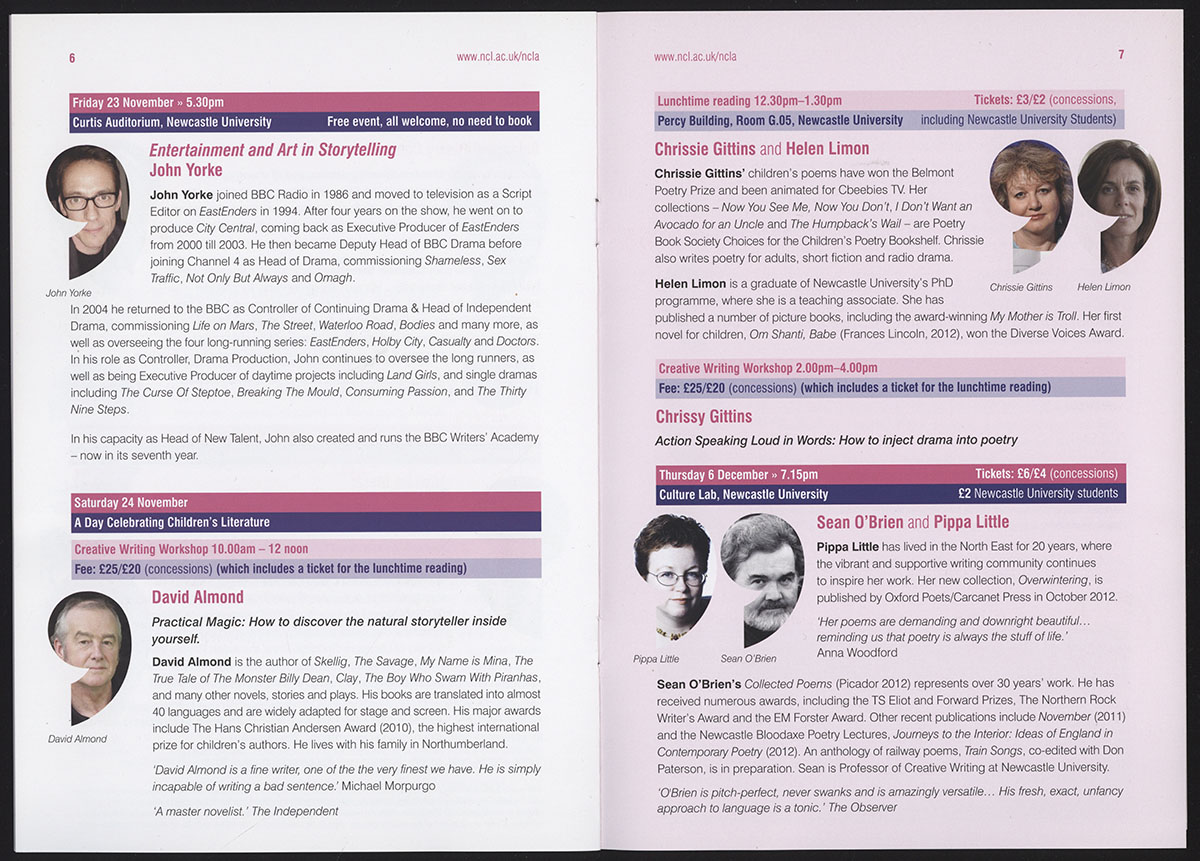

33:50: In talking through his views on the relationship between poetry and the audience, O'Brien mentions the Newcastle Centre for the Literary Arts. The NCLA has hosted a lot of good events, which have drawn large audiences. O'Brien feels this shows that you don't have to sell literature short in order to interest the public. He believes literature should be popular but it shouldn't gain its popularity by demeaning itself or pretending to be less complicated than it is. Events that have been hosted by the NCLA in the past show there is a public appetite for poetry.