Selima Hill

Collected Voices

Selima Hill (née Wood) was born in 1945 in Hampstead, London, into a creative family; both her parents were artists, as were her grandparents. She won a scholarship to study Moral Sciences at New Hall College, Cambridge in 1965. After marrying in 1968 and starting a family in the 1970s, Selima published her first collection of poetry, Saying Hello at the Station, in 1984.

After winning the Cholmondeley Award for Poetry in 1986, Selima won the Arvon International Poetry Competition in 1989 for parts of her collection The Accumulation of Small Acts of Kindness, first published in 1988. In 1997, her collection Violet was shortlisted for three British poetry awards: the Forward Prize, the T. S. Eliot Prize, and the Whitbread Poetry Award. She was also shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize for her 2001 collection, Bunny, which won her the Whitbread Poetry Award. Her work has been recognised numerous times by the Poetry Book Society; her collections Violet (1997) and Bunny (2001) were both Poetry Book Society Choices, and her collections Lou Lou (2004) and The Hat (2008) were also Poetry Book Society Recommendations.

Selima has held various posts related to her work as a poet. In 1991, she was awarded a Writing Fellowship at the University of East Anglia, and was writer-in-residence at the Royal Festival Hall in 1992, and at the Science Museum in London in 1996. She has taught creative writing courses at hospitals and at HMP Norwich, and also been a tutor at Exeter and Devon Arts Centre in the 1990s.

On her relatonship with her publishers

On her writing process

On publishing her first collection Saying Hello at the Station

On the extent to which she feels part of a community of poets

On the key themes of her writing

On winning her first poetry award

Interview Summary

00:24 Selima begins by discussing how she has always been a writer. She states that her earliest memory was when parents wanted her to go to a Roman Catholic Convent, but she wasn’t a catholic. Her father took a poem to try to convince the Reverend Mother that Selima should join and Selima recognises that this was her parents clearly encouraging her to write.

01:18 Selima states that she is only a writer in as much as she is not a painter.

01:54 She discusses what drew her to poetry, stating that as a young woman, she was quite restless and poetry seemed more ‘portable’ so she could carry her notebook with her to write little ‘snippets’ of things constantly. Selima was encouraged as a young child to read poetry. She recalls that Robert Louis Stevenson, Walter de la Mare and Hilaire Belloc were all very familiar to her.

03:00 She discusses her experience of publishing her first poetry collection Saying Hello at the Station. At the time of publication, Selima was a young mother, with children at home, and says it was particularly difficult for her to think of herself as a writer. Andrew Motion had written to her, having seen some of her poems and asked her to send some to Chatto and Windus, where he was the editor. He asked if she had any work beside that which he had seen published here and there. At the time, Selima had 14 collections so they met and he edited a collection for her from her work – specifically those about Egypt.

04:50 Selima states that art is of extreme importance to her. She says that art has helped her to ‘make sense’ of her life. In her role as a teacher, particularly in prisons, she has tried to use art to help inmates express themselves. For Selima, art doesn’t necessarily answer any questions, but it asks them. She read Moral Sciences at Cambridge and recalls that students were encouraged to ask questions, but there were never any answers.

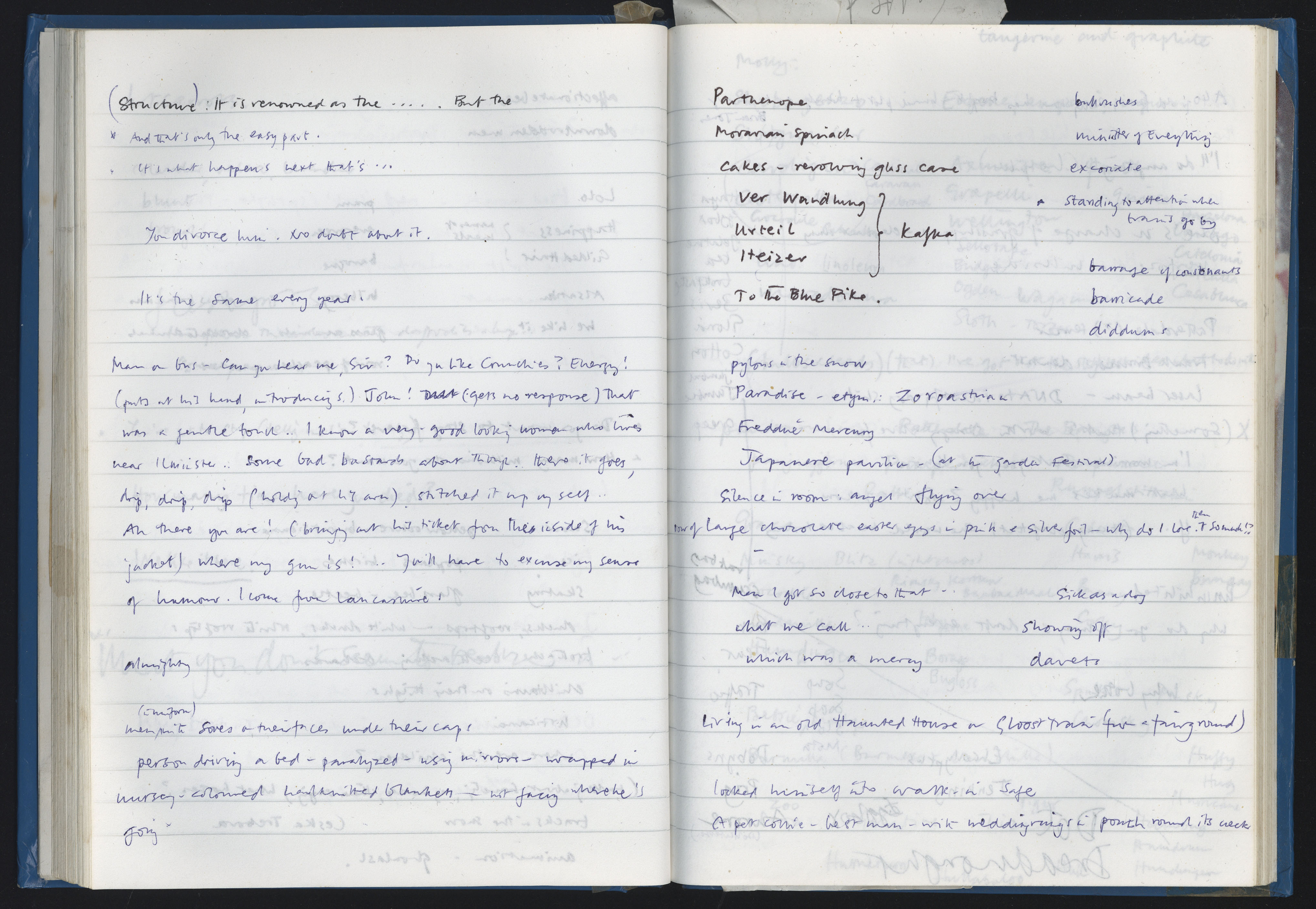

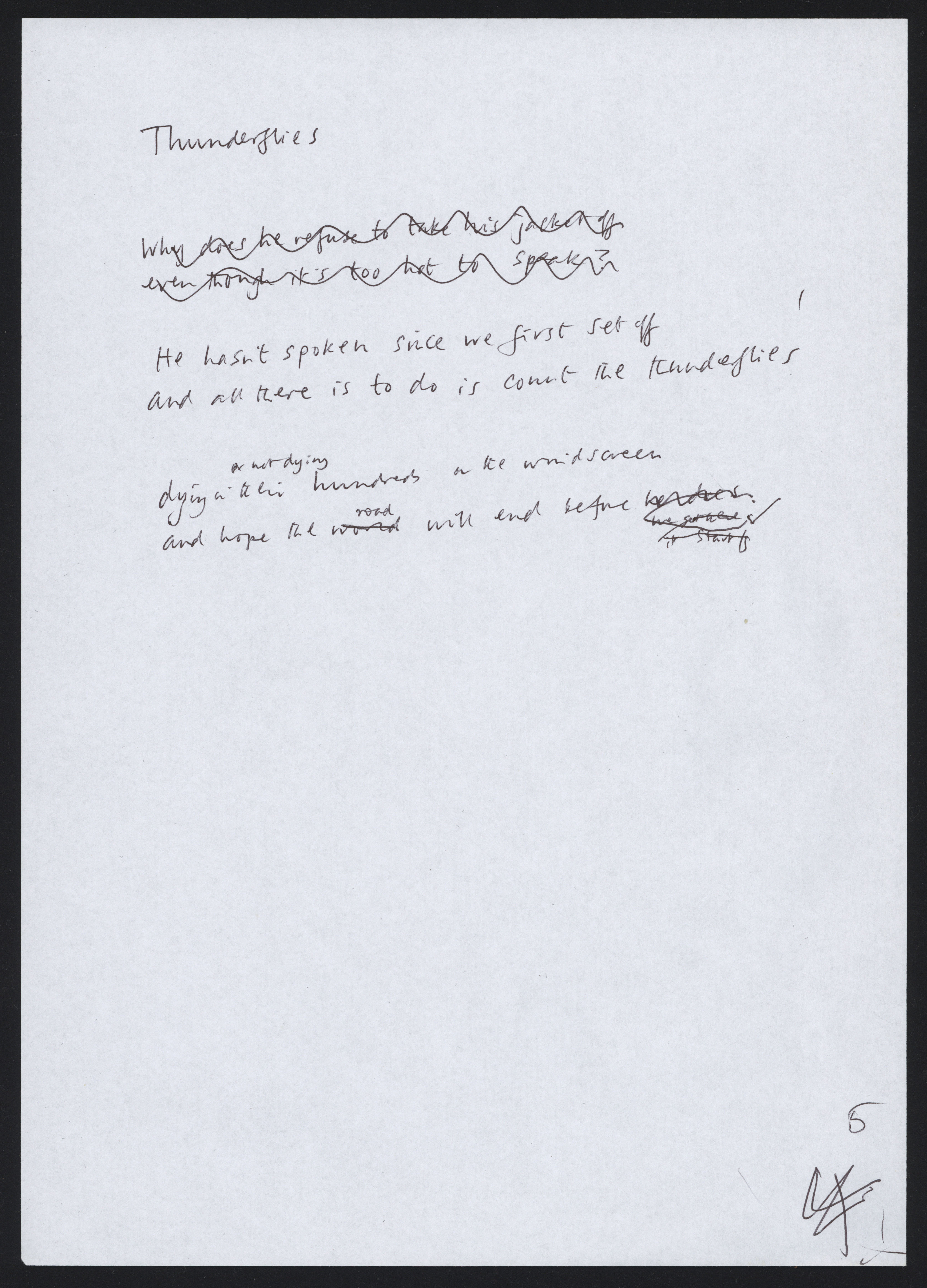

06:00 Selima describes her writing process and the role of notebooks – those close to her assume she is forever writing in her notebooks, as she does this even amongst company. She has a system of eight notebooks that she writes in simultaneously – each one for different aspects of her writing. She also illustrates these and uses them like scrapbooks. She states she finds it easier to express things in the written word, than orally.

08:06 Selima feels the key theme she explores in her poetry is her own self.

08:38 She describes her relationship with independent publishers as wonderful. She thinks it must be difficult for them as she hates being published and hates revisiting her work. While she identifies as a writer and an artist, she finds it difficult communicating this to other people. She feels much safer within the covers of a notebook, or a big white sheet of paper, than in any other situation. She has asked Neil [Astley] if she could publish under a different name but recognises he has spent a lot of time, patience and energy building a brand around her. However, she would feel safer and freer if she changed her name and she sometimes enters competitions under a pseudonym.

10:45 Selima feels a terrific sense of fellowship with other writers and artists. The world of poetry is very small but those within it gave her a tremendous amount of support when she was starting out.

11:30 Selima states that while she is a woman, and inhabits a woman’s body, she does often adopt the language of a highly educated male. This is, in part, due to her Cambridge education – which was very male-dominated. She states that some fellow poets found this tricky when she first started out.

12:30 Selima feels a stigma around her autism diagnosis, which didn’t come out until she left university.

13:10 Selima discusses her experience of the Opera Genesis project Beekeeper. She states it is hard to work as a team but she does love to try. It was a fascinating and exciting project – with everyone working on their different media. Selima recalls a lot of the project was sitting observing, which she thoroughly enjoyed as it was privileged access to other people working. During that time, Selima’s children were very young and she felt very torn between her identity as a mother, her identity as a wife and her identity as a writer. She felt quite marginalised when her male colleagues, and female colleagues without children, would go to the pub.

15:03 When Selima won her first award, she didn’t make a big deal out of this due to her still identifying as a mother. She finds praise particularly difficult, and the things she was being praised for in her work were those that she was derided for when she was younger: exaggeration and ruthlessness. Looking back, Selima wonders if her mother was afraid of her, since comparatively, Selima states she feels ‘bigger and stronger’ as an adult, than her mother. Her upcoming book I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid takes her mother as its subject matter.

17:36 For Selima, recognition from poetry prizes and awards is a confusing process, which she relates to her experience of publishing.

18:35 Selima discusses the gender divide that existed within her family – where men were more supported in their careers and her own academic achievements were side-lined following the birth of her children.

20:46 Selima states that you can’t ‘teach’ writing but she does enjoy sharing her enthusiasm. She tries to help people see what it is like to write without a particular type of literary education. Selima has taught writing in prisons, which she thoroughly loved. She related to the prisoners sense of being an ‘outsider’ and rejecting authority.

24:04 For Selima, there is a terrific difference between the performance and the written version of her poems. She spends a lot of time on the grammatical elements of poems that often are invisible during performance. In spite of being shy, she does enjoy reading her poems – she is alone and safe on stage and feels a terrific sense of fellowship with other poems.

25:46 Selima feels safe travelling since whilst travelling she states you can ‘be who you want to be’.

26:36 Depositing her archive feels like a construct to Selima – it is separate and removed from her. In spite of there being a lot of personal material in her archive, there was no curation of this on Selima’s part.

28:10 She hopes that people will look at her archive and realise it is okay to be a mother, writer and a woman altogether. She is overawed by the whole situation and grateful to those who have helped her along the way.